Introduction

In today’s society, many issues face young athletes. Sport participation can be a countermeasure to a sedentary lifestyle which is clearly prevalent and dangerous.

Often, individuals experience failed attempts to participate in organized physical development because too much emphasis is placed on competition, with little attention on developing proper athleticism (appropriate movement skills).

Individuals with limited sports and movement skills often stop participating. In turn, this neglect often leads to a decreased interest in any type of physical activity. The result is a failure to learn or develop physical literacy, or proper athletic movement in a sequential and progressive manner. A sedentary lifestyle then follows. Sedentary living causes such health problems as obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic diseases that evolve from a lifelong problem starting in childhood.

Despite this increased understanding, recent research evidence has shown declining fitness (Sandercock & Cohen, 2019) and physical activity levels (Tremblay et al., 2016), alongside an increased obesity prevalence among youth populations. Furthermore, young athletes within talent development programs have demonstrated reduced levels of motor skill. In addition, overuse injuries, which can be a result of early sports specialization, excessive load, under recovery, and/or physical underdevelopment, are also a major issue within youth sport populations.

A long-term commitment to physical literacy, proper training to improve athleticism, and sport skill development is vital to produce optimal athletic potential. Proper training and athletic development require time. Moreover, a paradigm shift needs to occur regarding the pace and process of athletic development. This paradigm shift has its own language:

There is no short-cut to success in athletic preparation. Overemphasizing competition in the early phases of training will always cause shortcomings in athletic abilities later in an athlete’s career.

The Concept of Athleticism

Youth sport pathways can have wide ranging increasing participation within sport for health, fitness, and physical activity outcomes to creating the sporting superstars of tomorrow within talent development and elite sport systems.

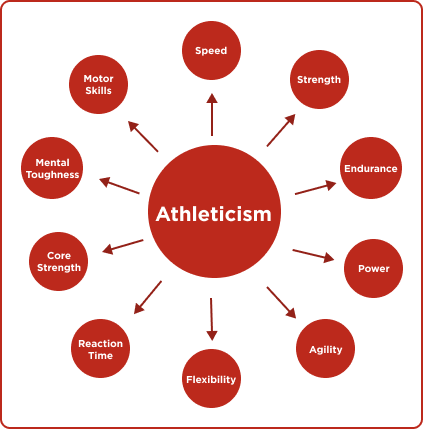

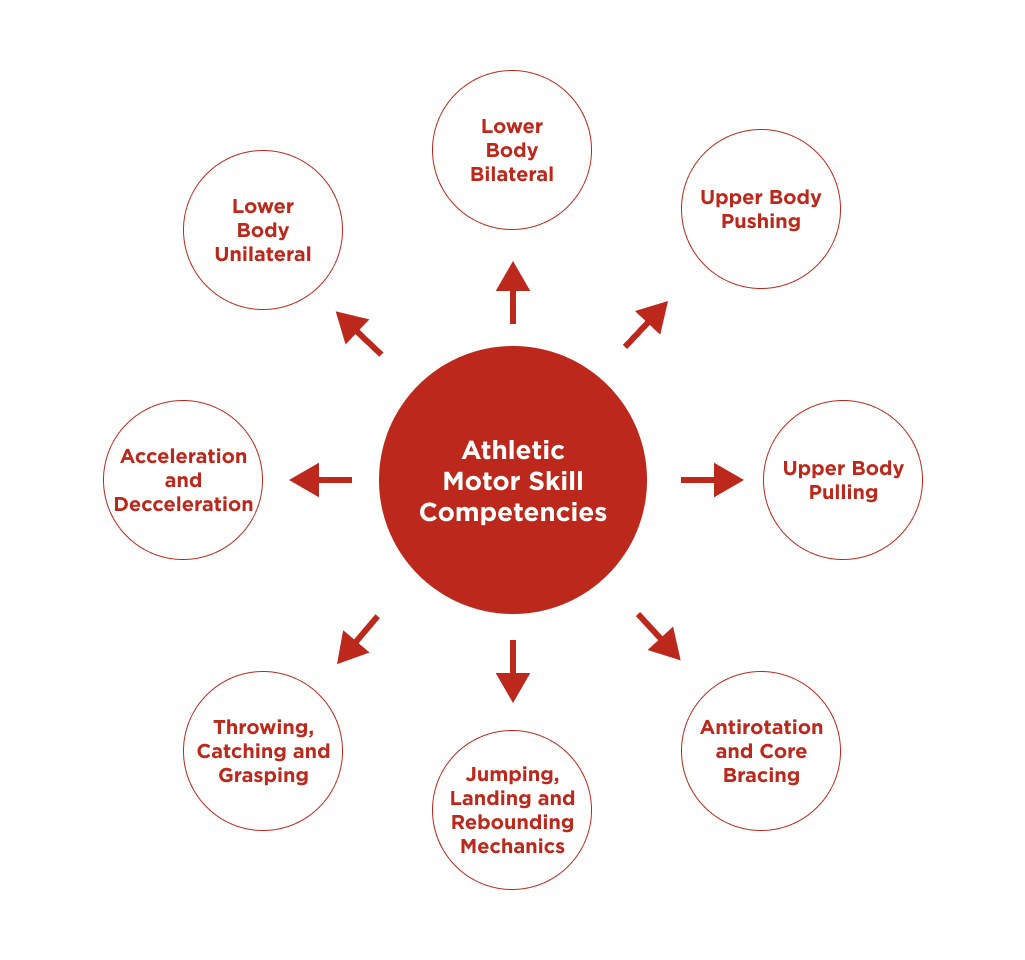

Athleticism has been defined as “the ability to repeatedly perform a range of movements with precision and confidence in a variety of environments, which require competent levels of motor skills, strength, power, speed, agility, balance, coordination and endurance”. It is well established that developing athleticism is important for health, physical activity, sporting performance, and injury risk reduction.

Physical Literacy

Physical literacy is defined as the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding to value and take responsibility for engagement in physical activities for life.

Physical literacy encompasses physical capacities embedded in perception, experience, memory, anticipation, and decision making. With this view, holistic participant development requires the development of physical, technical, tactical, and psychosocial skillsets.

Talent Development

Scientific research concludes that it takes 8 – 12 years of training for a talented athlete to reach elite levels. It also can be argued that it takes that long, if not longer, to produce quality youth coaches who understand how to develop proper skills in children.

There are no shortcuts to athletic success. Unfortunately, some coaches and parents overemphasize competition, while at the same time, approach proper movement skills and development to improve athleticism with little or no interest. A well-planned and balanced schedule of training, practice, competition, and recovery will enhance optimum development throughout the individual’s athletic career.

Early vs Late Specialization

Sports can generally be classified as early specialization or late specialization sports. Early specialization refers to the fact that some sports, such as diving, figure skating, gymnastics, rhythmic gymnastics, and table tennis require early sport-specific specialization in training.

Late specialization sports, including track and field, combative sports, cycling, racquet sports, rowing and all team sports require a generalised approach to early training. For these sports, the emphasis during the first two phases of training should be on the development of general motor and technical-tactical skills. Early specialization sports require a four-phase model, while late specialization sports require a six-stage model.

Early specialization model:

1. Training to Train stage

2. Training to Compete

3. Training to Win

4. Retirement / retainment

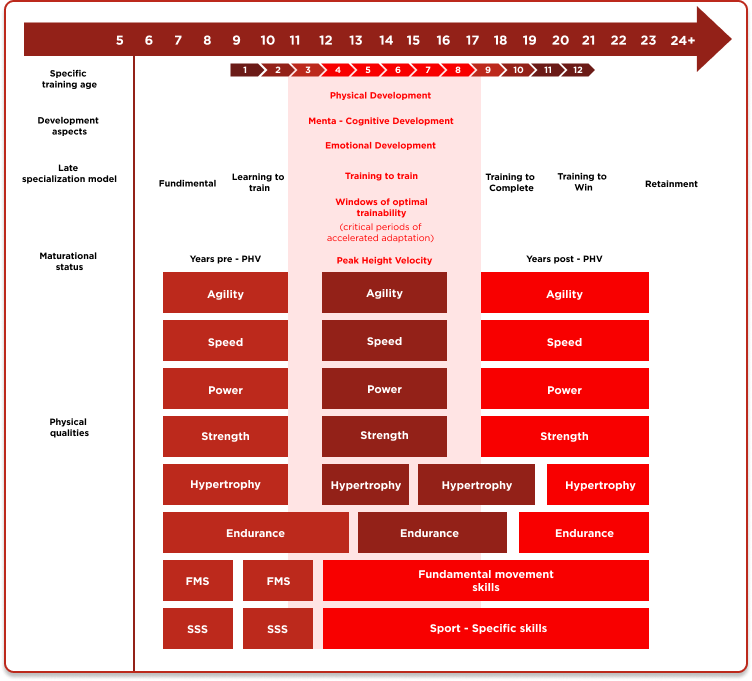

Late specialization model:

1. FUNdamental stage – Learn all fundamental movement skills (build overall motor skills);

2. Learning to Train – Learn all fundamental sports skills (build overall sports skills);

3. Training to Train – Build the aerobic base, build strength towards the end of the phase and further develop sport-specific skills (build the “engine” and consolidate sport specific skills);

4. Training to Compete – Optimize fitness preparation and sport, individual and position- specific skills as well as performance (optimize “engine”, skills and performance);

5. Training to Win – Maximize fitness preparation and sport, individual and position specific skills as well as performance (maximize “engine”, skills and performance);

6. Retirement / retainment – Retain athletes for coaching, administration, officials, etc.

Principles guiding proponents of early sports specialization:

1. Elite athletes specialize earlier than less successful athletes.

2. Elite athletes begin sport-specific training at an earlier age than less successful athletes.

3. Elite athletes have more hours of specific training throughout their careers than less successful athletes.

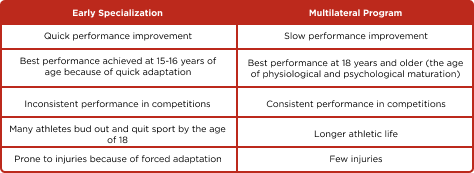

There are also different points of view that highlight the negative aspects of early specialization on psychological, social, physical and overall sports development. If children at the beginning (6-10 years old) are involved in highly structured sports programs in which the emphasis is on directed (thought-out, structured, formal-specialized) training with little free play, fun and entertainment, they quickly lose interest, become dissatisfied, disappointed and unmotivated for further work. The result is most often burnout, giving up, getting injured, changing the sport / program or completely abandoning it.

Bompa emphasizes the importance of proper understanding and application of the principles of specialization in children and young people. Multilateral training is the basis from which specialization develops.

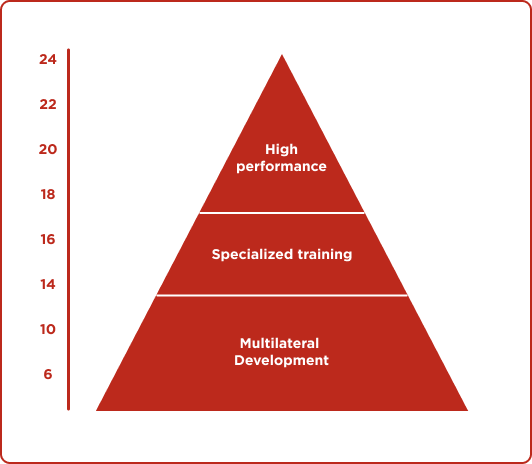

It’s important for young children to develop a variety of fundamental skills and to become good general athletes before they start training in a specific sport. This is called multilateral development, and it is one of the most important training principles for children and youths.

If we encourage children to develop a variety of skills, they will probably experience success in several sporting activities, and some will have the inclination and desire to specialize and develop their talents further. The base of the pyramid, which we may consider the foundation of any training program, consists of multilateral development.

When the development reaches an acceptable level, athletes specialize in one sport and enter the second phase of development. The result will be a high level of performance. The purpose of multilateral development is to improve overall adaptation. Children and youths who develop a variety of skills and motor abilities are more likely to adapt to demanding training loads without experiencing stresses associated with early specialization.

Child with no Training Experience and Low Technical Competency

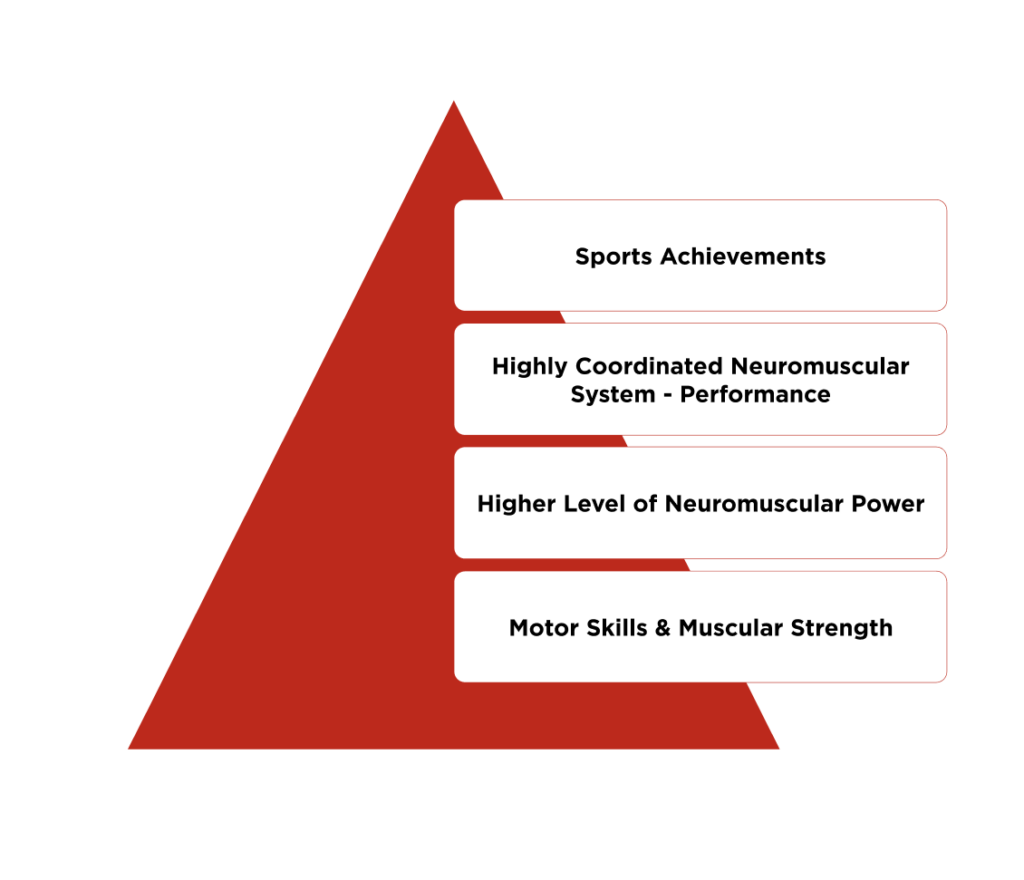

When a young child is first exposed to a formalized strength and conditioning program, it is unlikely the child will be able to demonstrate competency in a range of motor skills. Consequently, initial focus should be directed toward developing a diverse range of motor skills that will benefit overall athleticism.

Before trying to develop muscular power, coaches should look to increase muscular strength levels because an untrained child with low technical competency will be a considerable distance from his or her ceiling potential of force-producing capacities.

Therefore, in addition to training motor skills, base levels of muscular strength should also be trained during the early stages of the training program to enable the expression of higher levels of neuromuscular power. This approach should also provide a robust and highly coordinated neuromuscular system that youth can use to withstand the reactive and unpredictable forces typically experienced within free play, sports, or recreational physical activity.

Children with low technical competency should also be exposed to a range of activities that enable the simultaneous development of other fitness qualities, such as coordination, speed, power, agility, and flexibility.

Strength and conditioning coaches should not focus on one or two motor skill competencies, but should rather provide complementary training activities that develop a wide range of fitness components.

Additionally, a varied and holistic approach to athletic development is necessary from a pedagogical perspective in order to keep training sessions fun, interesting, and motivating for the young child.

In terms of developing neuromuscular power, practitioners should view childhood as an opportunity to lay the foundation of general athleticism that will then enable youth to participate in more advanced training strategies as they become more experienced.

Another example could be in the development of weightlifting ability, whereby childhood should be viewed as an opportunity to develop basic motor skills that will help in the execution of full weightlifting movements and their derivatives as technical competency improves.

Early vs Late Maturing Individuals

Because of the highly individual timing of maturation, it is imperative that any LTAD (long-term athletic development) model contains a degree of flexibility. An early maturing child has previously been defined as a girl or boy who starts their adolescent growth spurt approximately 1.5 or 2 years earlier than a late maturing child.

Although research has indicated that eventual adult height is not affected by early or late maturation (Hägg & J Taranger, 1991), strength and conditioning coaches must appreciate that an early or late maturing child will need to be treated somewhat differently than an “average” maturing child, when prescribing long – term athletic development programs.

In relation to the YPD (youth physical development) model, if a child is deemed to be an early maturer, then the components of the model will need to be moved to the left, thus enabling the child to begin more advanced training techniques at an earlier chronological age.

In contrast, a strength and conditioning coach must allow the components of the YPD model to be moved to the right for a child who is deemed a late maturer, thereby introducing them to more advanced training at a later chronological age, when they are physiologically ready to cope with the increased training stimulus.

The Youth Physical Development Model

The LTAD model suggests that there exist critical “windows of opportunity” during the developmental years, whereby children and adolescents are more sensitive to training-induced adaptation. The model also states that a failure to use these windows will result in the limitation of future athletic potential.

Authors identified that spurts in speed and endurance occurred before and around PHV (peak high velocity), respectively, whereas accelerated gains in strength qualities occurred after PHV. Using PHV as a key reference marker of maturation, the LTAD model proposes that these periods of accelerated adaptation offer windows of opportunity where training responses will be maximized. In the LTAD model, it is assumed that these periods of rapid natural development represent a time of increased sensitivity to training.

A Holistic Approach to Identifying Skills Needed for

Athlete Development

Technical skills are the basic skills that every athlete should possess in order to practice their sport at a certain level of competition or stage of sports development (initial, development, specialization stage, peak performance stage).

Tactical skills are problem-solving skills that are based on the player’s ability to “read the game”, “read the situation” and make decisions.

Physical skills involve preparing the body (athlete) to successfully respond to the physical demands of sport. They usually include strength, speed, power, endurance, flexibility, agility.

Mental skills are developed and improved through psychological training, and cover a wide area, starting from motivation, competitive orientation, self-confidence, self and collective efficiency, competitive anxiety, stress management skills, concentration and attention skills, up to emotional control, positive team climate, cohesiveness, team unity and the like.

Communication skills as a process of conveying messages.

Fair play refers to respecting the rules of the game (sport), which are necessary so that all participants have an equal chance of winning.

Sportsmanship is good character when participating in sports.

Character represents the sum of our habits, a unique assortment of virtues and vices. In sport, it means self-control, conscientiousness, honesty, responsibility towards oneself and others (coach, teammates, referees, staff), perseverance, persistence, willingness to cooperate, understanding and compassion, honesty, respect, politeness, fairness.

Conclusion

Strength and conditioning for young athletes shouldn’t just be about improving performance but also about helping them develop healthy habits and laying the groundwork for a long-lasting athletic career. A well-planned training program that includes all components of fitness and is age-appropriate can prevent injuries and lead to peak performance in the future.

References

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18981934/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30098974/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15938474/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27848745/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27848745/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25909962/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30285701/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28934100/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17805079/

Psihološke osnove treniranja mladih sportista, Ljubica Bačanac, Nebojša Petrović, Nenad Manojlović