Introduction

To say that performance in football depends on a variety of individual skills and abilities, but also, of course, on the interactions that each player establishes with teammates and opponents, should not, in principle, raise much objection. In fact, technical and tactical abilities are determining factors, but in order to be successful, each player must be able to improve his or her individual physical skills.

The Importance of Sprinting in Modern Football

Among these skills, given the paramount importance it assumes in this context, it is possible to highlight the ability to repeatedly run at high speed during a game. In this context, the aim is to reflect, in an unpretentious way, on various aspects of sprinting in the context of current football practice, seeking to contribute to clarifying this topic.

High-Intensity Running and Injury Risk

In fact, the specialized literature has increasingly focused on the anaerobic demands of football and an increase in the high-intensity distances (>19.8 km/h) and sprint distances (>25.2 km/h) that a player performs in competition has been recorded, values that tend to increase at higher competitive levels.

At the same time, the epidemiology of the sport describes hamstring rupture as the most frequent injury in football (12% of all injuries), with around 70% of these situations occurring during sprinting, and age and previous injury being identified as the greatest risk factors. This allows us to conclude that the most frequent injury mechanism (sprint) for the most frequent injury in football (hamstring muscle rupture) has been occurring increasingly in the context of game.

Specificity of Sprint Training

Therefore, the question is how we can prevent these situations from occurring, or in other words, understand whether it is possible to prepare players in order to minimize the risk of injury.

It is clear that speed training is highly specific. This means that sprinting tends to naturally improve a player’s ability to sprint at maximum speed. As such, not only as a training tool but also as a factor in reducing the risk of injury, it is essential to expose players to high-intensity running. In this sense, I believe that exercises that promote this stimulus should be included in training, proposing, in particular and among others, exercises with more space in length than in width, which will promote deep and high-intensity running actions, with the aim, for example, of reaching the opponent’s goal.

Monitoring Sprint Load with Technology

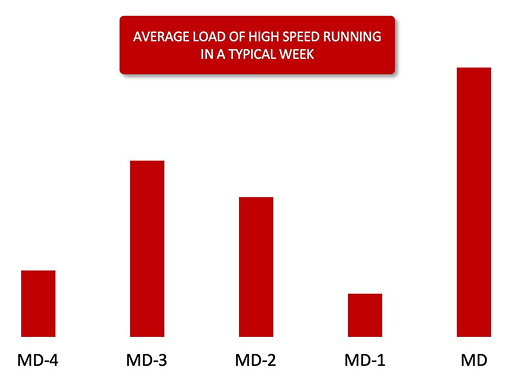

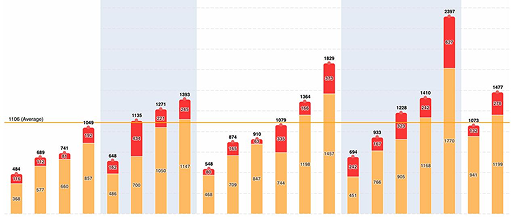

The ideal would be to ensure the availability to collect specific data on acute and chronic loads, based on the distances covered and sprints performed, both in training and in competition, using GPS devices or tracking systems, with the use of cameras installed for this purpose. When necessary, this work should be carried out analytically, to ensure that all players receive this exposure, in the quantity and intensity appropriate to their position, based on what is specifically required of them in the game. If this does not happen, the possible practical consequences will be unpredictable.

The Role of Kinetics and Kinematics in Sprinting

In addition to this exposure to high-intensity running, there are components of players’ running performance that can be worked on simultaneously, using the input of kinetics and kinematics. Kinematics, an area that, applied to this context, analyses the movement of biomechanical segments during running, and kinetics, which relates this movement to the forces that cause it, tend to be undervalued.

However, they are complementary areas and are particularly relevant in various aspects of speed training. In fact, it is crucial that the player is trained to efficiently apply large amounts of force in the supports he performs.

Eccentric Demands and Hamstring Preparation

And this, evidently, because the better prepared the player is to perform high-intensity runs, repeated over time and, eventually, under fatigue, the better his performance will be and the lower the risk of injury he will be subject to. Despite this, it is not only the amount of force applied that matters, but also the way in which this force is applied.

Let us suppose, for example, that a player, during the run, performs greater flexion of the thigh in the mid-swing phase. This will lead to a greater force applied to the ground in the subsequent support. However, if this support is carried out in front of the projection point of the center of mass on the ground, part of the force will be applied in the opposite direction to the displacement, a circumstance that will be counterproductive.

Sprint Training Under Fatigue Conditions

Another practical example of the importance of these areas for the aforementioned training is the need to prepare the posterior thigh muscles for performing explosive actions. However, this alone will not be enough, since performing a sprint incorporates these explosive actions in large muscle amplitudes.

The hamstrings, biarticular muscles made up mainly of type II fibers, will be required in a large-amplitude eccentric action with enormous traction force, which occurs mainly in the early stance phase, and at this point a possible muscle injury may occur (although there is no consensus, this moment is identified in a significant part of the specialized literature as being the one where hamstring ruptures most frequently occur). Hence the need to perform specific training, including in situations of fatigue, aimed at minimizing the risk of this type of injury occurring.

High-Speed Running in Return To Play Protocols

Kinetics and kinematics are undoubtedly key elements in high-speed running training, as they allow for a more in-depth understanding of the sprint mechanism. This understanding will help the person responsible for prescribing training, not only when designing exercises, but also when defining strategies for returning to practice after injury. Furthermore, in a Return To Play process, it is essential that players are progressively subjected to high-intensity and sprint distances until the applied load is equivalent to that which they will encounter when they are integrated into training with the rest of the team (final phase of the RTP process).

Conclusion: Sprint Preparedness as a Performance and Safety Factor

In short, if we consider that footballers inevitably have to perform sprints at high speeds during the game, it is essential that they are prepared to perform this type of action. In order for the player to maintain/improve their performance and be available for this effort in competition, good prior preparation is essential, which takes into account the mechanisms of running and the epidemiology of the sport.