From Mechanical Cost to Match Week Monitoring in Football

Introducción

In season load monitoring, most teams track familiar external load variables such as total distance, high speed running, sprint distance, and accelerations. Increasingly, however, decelerations are emerging as a particularly informative signal, not because they reflect “more running,” but because they represent a distinct mechanical stress (Harper, 2023; McBurnie, 2021).

A recent football study applied an ACWR framework to GPS derived workload variables to examine which signals best differentiated injury and non-injury weeks in professional players. Within this modelling approach, deceleration related workload ranked among the strongest performing indicators, leading the authors to position deceleration as a key input for future multivariable injury risk frameworks (Saberisani et al., 2025).

Building on this, in this blog we are going to look at the mechanical demands placed on the athlete’s body during decelerations, explain monitoring of maximal deceleration load using ACWR, and show which days in the weekly microcycle focus on most for tracking and managing this exposure.

Mechanical Demand of Decelerations

Horizontal decelerations can be defined as locomotor actions in which the athlete rapidly reduces whole-body momentum, typically after a sprint or before executing a change of direction, tackle or stop. In intermittent multi directional sports, these braking steps account for a substantial proportion of high-intensity movements and are closely associated with both key performance actions, and typical non-contact injury mechanisms such as ACL rupture. (Harper, 2023; Verheul, 2024).

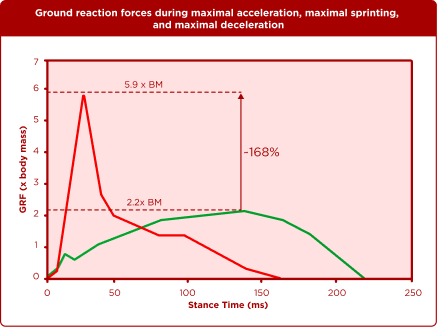

From a mechanical standpoint, high intensity decelerations expose the athlete to external loads that are markedly greater than those observed during acceleration or maximal sprint. Ground reaction force (GRF) data demonstrate that when an athlete brakes from near-maximal sprinting, peak vertical GRF during the initial deceleration step can reach approximately six to eight times body weight, which represents roughly one-and-a-half to three times the external loading seen during accelerated or high-speed running.

The anteroposterior component of the GRF is even more distinctive, with peak braking forces several-fold higher than in other locomotor tasks, reflecting the need to generate a substantial opposing impulse to reduce horizontal centre-of-mass velocity. Crucially, these peak forces occur very early in stance, typically within the first 30–50 ms after foot contact, resulting in very steep force time curves and high loading rates that place considerable demands on the neuromuscular system’s ability to attenuate impact (Verheul, 2024).

The stance phase of a deceleration step can be conceptualised in three overlapping mechanical phases, each characterised by a specific combination of external and internal loads. Immediately following touchdown, there is an impact dominated phase in which GRF rises rapidly, and substantial axial “bone on bone” loads are transmitted through the ankle, knee and hip. Inverse dynamics and musculoskeletal modelling showed that ankle joint contact forces were the largest of all joints, with average peak values of about 24.5 ± 9.5 times body weight clearly elevated compared with steady-state running (Verheul, 2024).

As the stance phase progresses, a support and braking phase follows in which large internal ankle plantarflexion and knee extension moments are required to maintain limb stiffness and control the deceleration of the centre of mass against the continuing external GRF. In the final portion of stance, high knee extension moments persist while the system completes the reduction in forward velocity and prepares to transition into the next step or manoeuvre (Verheul, 2024).

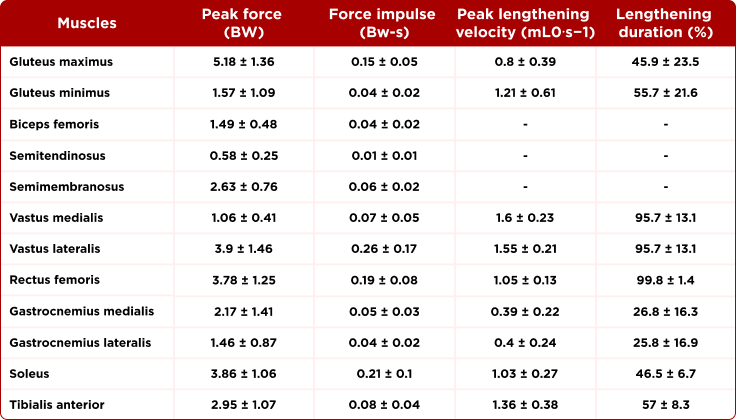

At the tissue level, decelerations impose pronounced eccentric demands on several key muscle groups. Quadriceps musculature, particularly the rectus femoris and vasti, is central to attenuating braking loads these muscles produce high knee extension moments while lengthening throughout much of stance and, in modelling work, have been estimated to generate forces up to approximately 5.5 times body weight at the highest lengthening velocities recorded among lower limb muscles during the task.

This combination of elevated eccentric force and high fascicle shortening lengthening velocity is strongly associated with exercise induced muscle damage, neuromuscular fatigue, and transient reductions in force generating capacity. The gluteal musculature also plays an important eccentric role, resisting rapid hip flexion under the influence of large horizontal braking forces and producing forces reported in the region of 6.5 times body weight.

Distally, the tibialis anterior and soleus contribute to the control of ankle kinematics during early stance, developing forces of roughly three to four times body weight while absorbing the rapid dorsiflexion plantarflexion demands imposed by the impact. Although hamstrings forces during ground contact in pure deceleration appear less extreme and more concentric in nature, their lower absolute capacity and their involvement in subsequent high speed actions mean that accumulated braking load may still interact with other factors (for example, fatigue, sub optimal trunk pelvis control) to influence injury risk (Verheul, 2024).

Deceleration demands also need to be considered at the level of repeated exposure rather than as isolated events. Match analysis work in football shows that high-intensity horizontal decelerations occur frequently across the duration of a game, and that they constitute a large proportion of the highest-magnitude (>6–8 g) impacts captured by wearable sensors.

When mechanical cost is expressed per metre of displacement, intense decelerations typically exhibit greater load per unit distance than accelerations or other running activities within the same nominal intensity band, indicating that braking is disproportionately “expensive” from a mechanical perspective (Harper, 2023; McBurnie, 2021).

Over congested fixtures or poorly managed training periods, repeated exposure to these high-force, high loading rate braking steps is therefore likely to contribute substantially to cumulative tissue stress, residual soreness and decrements in neuromuscular function (McBurnie, 2021).

Deceleration Load Monitoring and Unidimensional Modelling

The mechanical profile outlined above suggests that decelerations represent a distinct and “costly” component of external load. This view is supported by recent work that has examined how deceleration exposure behaves within a season long injury “prediction” framework. Saberisani et al. analysed training and match data from one Iranian Premier League squad (25 outfield players, 214 training sessions and 34 matches) across a full competitive season, combining GPS derived external load metrics with a decision tree classifier in a unidimensional design (Saberisani et al., 2025).

External load was quantified using a 10 Hz GPS system, with seven weekly variables retained for analysis: total distance, average total distance, distance covered at high and moderate speeds (19.8–30.0 km·h⁻¹), total distance load (distance × average speed), accelerations (>4 m·s⁻²), decelerations (<–4 m·s⁻²), and an ACWR value for each variable calculated using a 1:3 week ratio (acute week divided by the mean of the previous three weeks) (Saberisani et al., 2025). Injury was defined as any time loss incident, and weeks were classified dichotomously as “injury” or “no injury” based on the occurrence of at least one such event.

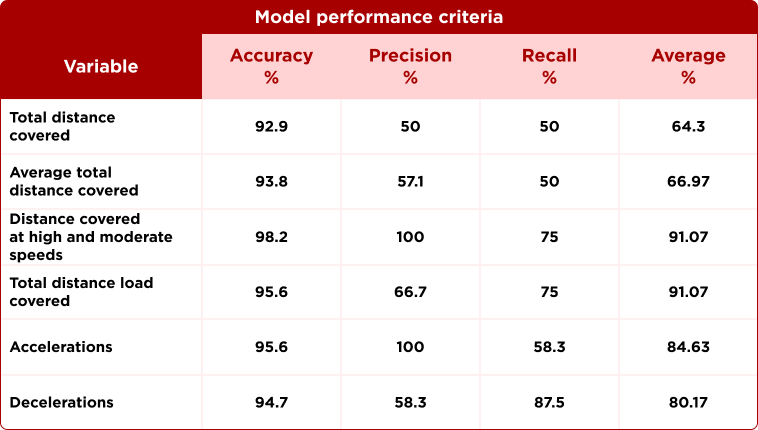

To evaluate the predictive contribution of each GPS variable, the authors ran a separate decision tree model for every ACWR metric, using an 80:20 train test split and four standard performance indices: accuracy, precision, recall and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) (Saberisani et al., 2025). This paper avoided building a multivariable model, instead, the aim was to identify which single external load variables showed the most promising discrimination between injury and non-injury weeks so that they could be prioritised for future multidimensional approaches (Saberisani et al., 2025).

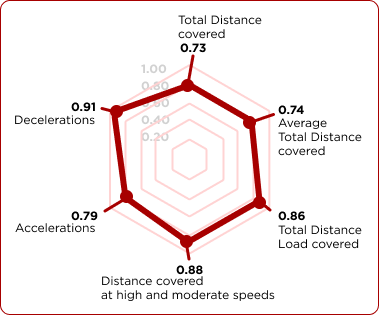

Across the seven variables, none achieved “very high” predictive performance (AUC > 0.95), and the authors explicitly caution against viewing any single metric as a stand-alone injury prediction tool (Saberisani et al., 2025). Nevertheless, the deceleration of ACWR emerged as one of the most informative indicators. In the test set, the deceleration model yielded an AUC of 0.91, a recall of 87.5%, a precision of 58.3%, and accuracy of 94.7% (Saberisani et al., 2025).

In simple terms, the model correctly identified a large proportion of injury weeks when deceleration ratios deviated from the athlete’s preceding three-week profile, while the false-positive rate remained moderate. When all four-performance metrics were considered jointly, the combined distance at high and moderate speeds variable displayed the highest overall scores (accuracy 98.2%, precision 100%, recall 75.0%, AUC 0.88) (Saberisani et al., 2025).

These AUC results are illustrated in Figure 4 of the paper, where each variable occupies one arm of a radar chart. Decelerations (AUC 0.91) and distances covered at high and moderate speeds (AUC 0.88) form the longest arms of the plot, followed by total distance load (AUC 0.86), whereas accelerations (AUC 0.79) and the more traditional volume metrics total distance (AUC 0.73) and average total distance (AUC 0.74) sit closer to the centre. Visually, the figure reinforces the quantitative finding that speed and deceleration based exposures carry much stronger signal for injury/non-injury discrimination than distance alone (Saberisani et al., 2025).

Methodological considerations are important when interpreting these findings. The sample was restricted to a single professional team with a relatively small number of injury events, which increases the risk that model performance is inflated by class imbalance and sampling variability. The ACWR itself has recognised limitations, and its capacity to prospectively predict injury has been questioned in larger cohorts. Nonetheless, within this constrained setting, the behaviour of deceleration ACWR is informative. It indicates that weeks in which deceleration exposure rises sharply relative to the previous three weeks are systematically over represented among injury weeks, more so than weeks characterised by comparable changes in total distance alone (Saberisani et al., 2025).

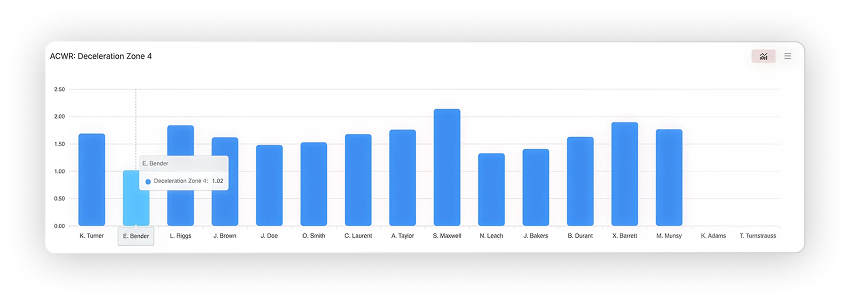

This conceptual role for deceleration of ACWR is reflected in the Ultrax “ACWR: Deceleration Zone 4” view (Figure 5). In this, squad level display, each bar represents the weekly ACWR for max intensity decelerations (Zone 4) for an individual player, calculated as the ratio between the current week’s exposure and the mean of the previous three weeks. Values close to 1.0 indicate that an athlete’s recent high intensity braking exposure is broadly aligned with their established chronic load, values substantially above 1.0 indicate an acute increase relative to baseline, and values clearly below 1.0 indicate relative under-exposure during the most recent microcycle.

From a monitoring perspective, this unidimensional model does not provide fixed “red-flag” thresholds, nor does it justify deterministic prediction. Instead, it supports the use of deceleration-based ratios as priority indicators within a broader decision support system. Given the mechanical profile of decelerations, high peak ground, reaction forces, steep loading rates and substantial eccentric demands on the quadriceps, gluteal complex, an increase in deceleration ACWR is likely to reflect a real change in neuromuscular load, even when traditional volume or speed metrics appear stable.

When combined with high/moderate speed running exposure, decelerations therefore offer a practical way to align external-load monitoring with the underlying tissue stresses described earlier (Saberisani et al., 2025).

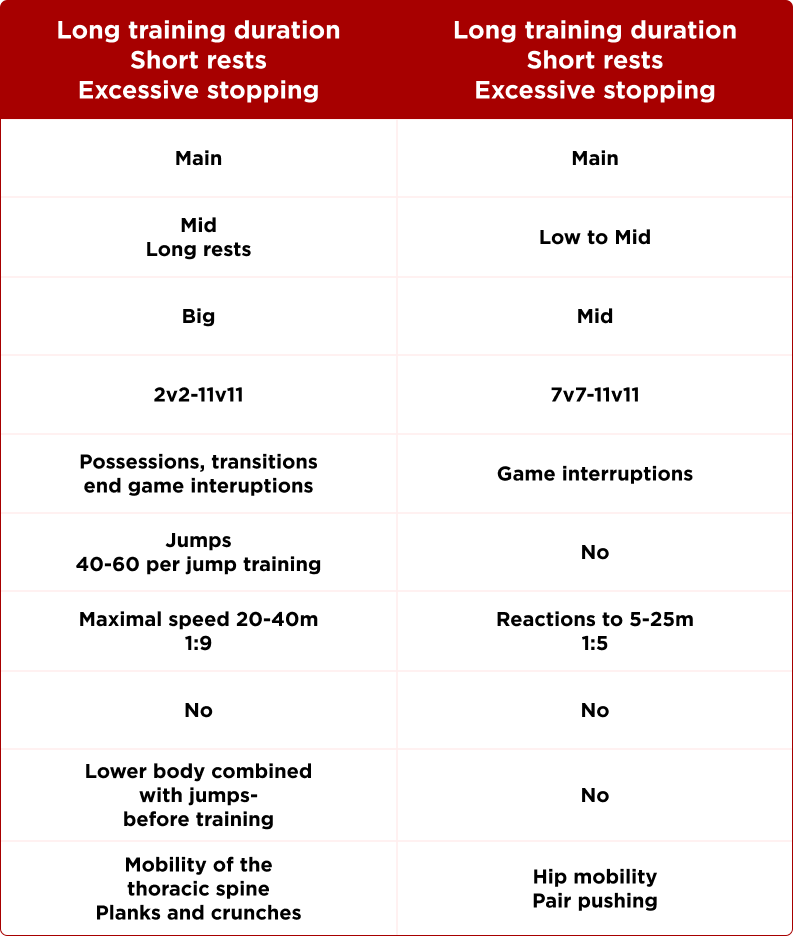

From a practical point of view, the first step is to map the weekly microcycle, mark the game, identify the high day, the lighter days and the recovery days. On top of that structure, decelerations can be organised into simple zones, Dec-2 m·s⁻², Dec-3 m·s⁻² and Dec-4 m·s⁻². Across the week there will always be a mix of all three, but it is realistic – and useful to expect that most Dec-4 exposures occur on the main high day, with much smaller volumes on MD-2 and MD-1. In other words, the heaviest braking should live where the microcycle is designed to tolerate it, not in the taper. In this framework, high-intensity deceleration Dec-4 m·s⁻², can be treated in a similar way to weekly near-maximal sprinting, as a kind of “vaccine” exposure that helps players maintain tolerance to the high forces they will face in matches.

A small, planned dose of Dec-4 m·s⁻², on the high day preserves the players ready for the match, keeping Dec-4 m·s⁻² very low on MD-2 and MD-1 helps avoid carrying extra eccentric fatigue into the game. If ACWR is then applied specifically to Dec-4 m·s⁻² decelerations, using the same 1:3 acute:chronic logic as for global load, practitioners can see both when the weekly dose of maximal braking is spiking and when players are being consistently under exposed.

MD-2 & MD-1: Deceleration Monitoring as Match Day Approaches

MD-2 is structured as a competitive training day around the main game model. The session uses big fields and formats from 2v2 up to 11v11, with possessions, transitions and end-game interruptions. That environment naturally creates frequent, often aggressive decelerations as players close space, press, recover and reset. Because the main part is long and the rest is short, these braking actions can accumulate quietly. On MD-2 the goal is to deliver a strong tactical and physical stimulus while keeping the number of very high-intensity decelerations under control, if Zone-3 and Zone-4 braking start to climb sharply here, it is a sign that extra eccentric load is being pushed close to the game.

On MD-1, the same basic session template is used. Intensities are kept high, but the volume is kept low, here we focus on quality of work not the quantity. The main content is 7v7–11v11 small-sided games with more frequent stoppages, and the only extra running is short reaction efforts over 5–25 m with a 1:5 work: rest ratio. This day should focus on keeping the players fresh and sharp without adding much mechanical stress. From a deceleration point of view, MD-1 MD-1 should add only a small amount of additional high-intensity braking, most decelerations should be lower-intensity zones. If monitoring shows that MD-1 is still driving upper-zone deceleration exposure, it usually points to something with the programming, SSG choice, work:rest balance, pitch size…that is unintentionally turning a light day into another heavy eccentric hit.

Conclusión

The evidence across mechanics, modelling and practice points in the same direction, decelerations are a distinct and costly form of load that deserves specific attention. High-intensity braking repeatedly exposes the lower limb to very large forces, steep loading rates and high eccentric demands, a profile that is different from both acceleration and steady running and is closely aligned with common lower-limb injury mechanisms.

Within season-long data, this shows clearly. In the Saberisani et al. model, deceleration ACWR was one of the most informative single signals, outperforming volume measures and sitting alongside high/moderate-speed running as a “sensitive” marker of weeks in which injuries occurred more often. The work is not a licence to “predict” injuries, but it is a strong justification for giving deceleration exposure a central place in monitoring.

Ultrax’s deceleration tools translate this into daily practice. Zone-specific ACWR profiles, and particularly the Deceleration Zone 4 ACWR view, make it easy to see which players are experiencing unusually high or low high-intensity braking relative to their own recent history. In the taper, MD-2 and MD-1 become deceleration management days, where extra spikes in high deceleration zones are avoided so that eccentric fatigue does not carry into the match.

Interested in diving deeper into this topic? Explore the physiological, neural, and neuromuscular foundations of deceleration in more detail here: https://www.ultrax.ai/trainings/unveiling-the-physiological-neural-and-neuromuscular-foundations-of-deceleration/

Referencias

Harper, D. J., & Carling, C. (2019). High-intensity acceleration and deceleration demand in elite team sports competitive match play: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sports Medicine, 49(12), 1923–1947.

McBurnie, A. J., Harper, D. J., Jones, P. A., & Dos’Santos, T. (2022). Deceleration training in team sports: Another potential ‘vaccine’ for sports-related injury? Sports Medicine, 52(1), 1–12.

Verheul, J., Harper, D., & Robinson, M. A. (2024). Forces experienced at different levels of the musculoskeletal system during horizontal decelerations. Journal of Sports Sciences, 42(23), 2242–2253.

Saberisani, R., Barati, A. H., Zarei, M., Santos, P., Gorouhi, A., Ardigò, L. P., & Nobari, H. (2025). Prediction of football injuries using GPS-based data in Iranian professional football players: A machine learning approach. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 7, 1425180.