Motivation for Investigation

There are several hundred thousand ACL reconstructions per year globally. One third of ACL reconstruction athletes reinjure within 5 months. Many of those athletes will have ongoing chronic knee problems for the rest of their life. This costs sports clubs an exorbitant amount of money in injured player salaries as well as medical costs. This ends careers.

Current practices predominantly use line of sight and touch to evaluate an athlete’s progress. For example, a physical therapist (PT) will monitor an athlete perform exercises or dynamic movements and score performance. This has low reproducibility between PT practices and even PT to PT which suggests that these metrics are subjective. However, it is important to note that these subjective metrics do not require equipment and are better than tracking nothing.

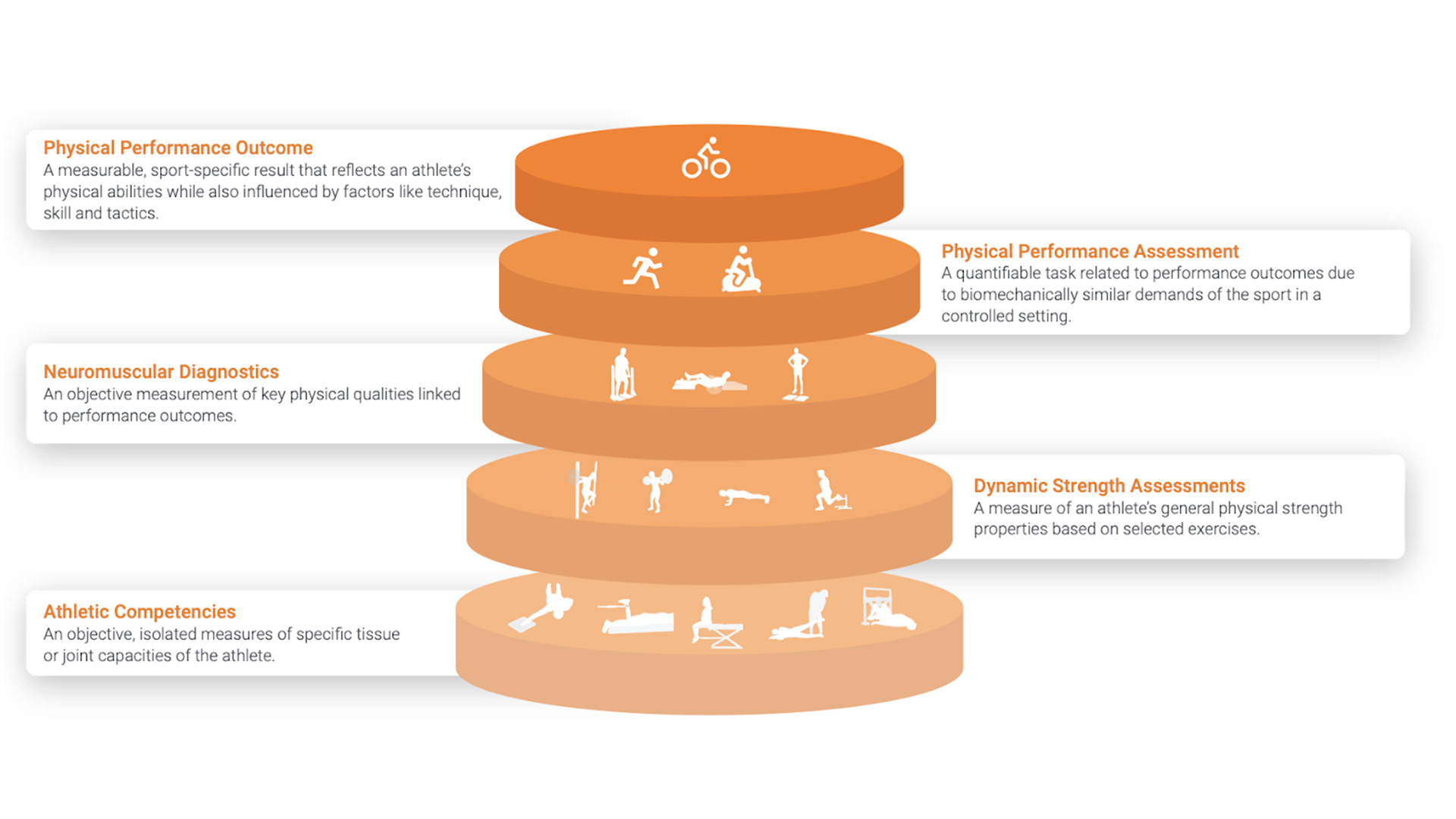

PTs also use some tools (ie. camera systems to analyze biomechanics, dynamometers to measure strength/power of muscle systems, etc.) to measure performance but nothing is fast to set up and wearable for functional movements. Furthermore, nothing actually measures what is going on inside the athlete’s body – these tools only measure the output. Nothing about the input – the neuromuscular control system. Nothing can measure how efficient the athlete is moving (input to output ratio).

Case Report 004 – ACL Rehabilitation

For this reason, this particular case study sought to understand:

- What is the neuromuscular behavior of “successful” rehabilitation? “Successful” rehabilitation being return of function to the injured leg such that it is within 10%performance compared to the healthy leg (ie. dynamometer and dynamic testing).

- Are there any markers that could indicate “unsuccessful” rehabilitation?

- Successful rehabilitation would result in improvements in movement efficiency.

Unsuccessful rehabilitation would result in little to no improvements in movement efficiency.In collaboration with MCZ Groningen, Oro Muscles conducted a small pilot study with 40+ athletes that had undergone recent ACL reconstruction due to a completely torn ACL. All athletes wanted to return to playing their sport. Most were young footballers under 25.

We monitored these athletes at multiple points in time in their rehabilitation. One evaluation was taken at the 3-5 month mark in their rehabilitation and at least another evaluation past 8+ months. We specifically compared their neuromuscular function at these particular timepoints to see if the rehabilitation was resulting in higher movement efficiency. We chose to monitor the vastus medialis (inside quadricep muscle) because it is a vital muscle involved in knee extension and stabilization. It undergoes soft tissue damage during ACL reconstruction and we used surface EMG to monitor its behavior during dynamometer testing.

During ACL reconstruction, the muscles around the knee are cut during surgery to access and reconstruct the ACL. Though return of structural integrity in the reconstructed ACL is fairly quick, the soft tissue damage takes at least 9 months to rehabilitate. Therefore, the rehabilitation of the soft tissue – mainly the muscles that were injured during surgery – is the main driver of time to return to play.

Current practice for ACL reconstruction rehabilitation is a template 9 month rehabilitation plan with two phases.

Phase I consists of basic isometric to eccentric movements of the knee extensor muscles (ie. leg extensions and hamstring curls) for 3-5 months. The focus of this phase is to build back lost muscle mass in the injured leg and strength.

Phase II consists of moving to more dynamic movements (ie. jogging, jumping, basic sports drills, etc.) until desired functionality is met. The focus of this phase is to recover neuromuscular pathways for dynamic movements and eventually performance.

Characterizing ACL Rehabilitation

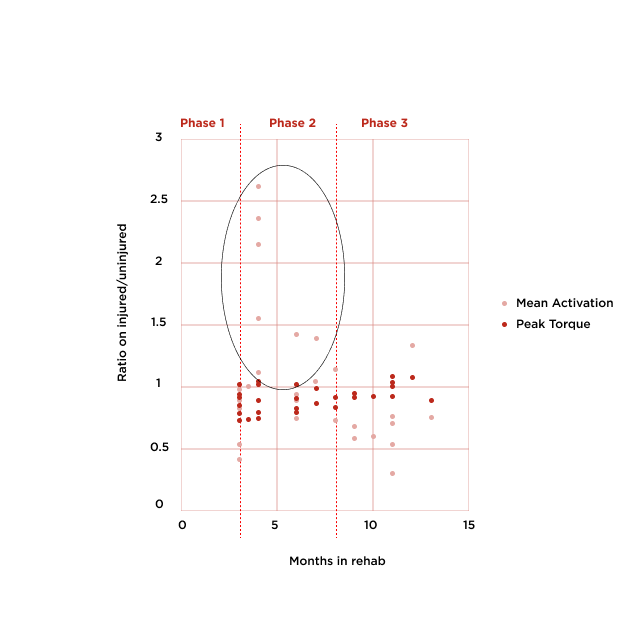

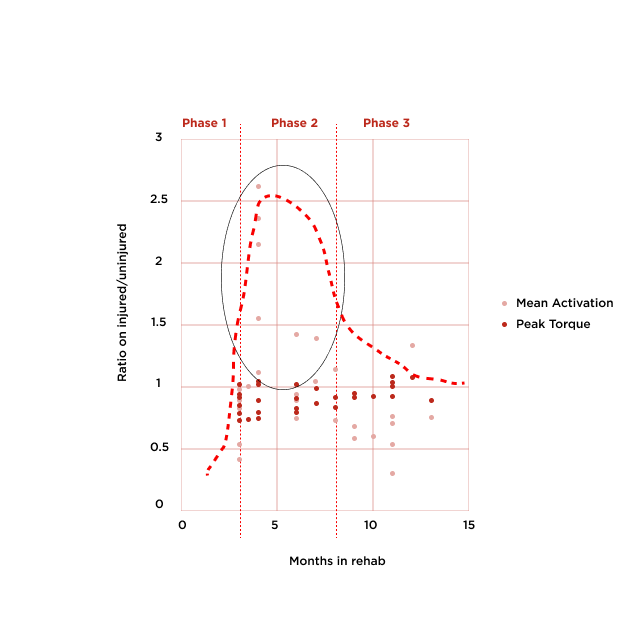

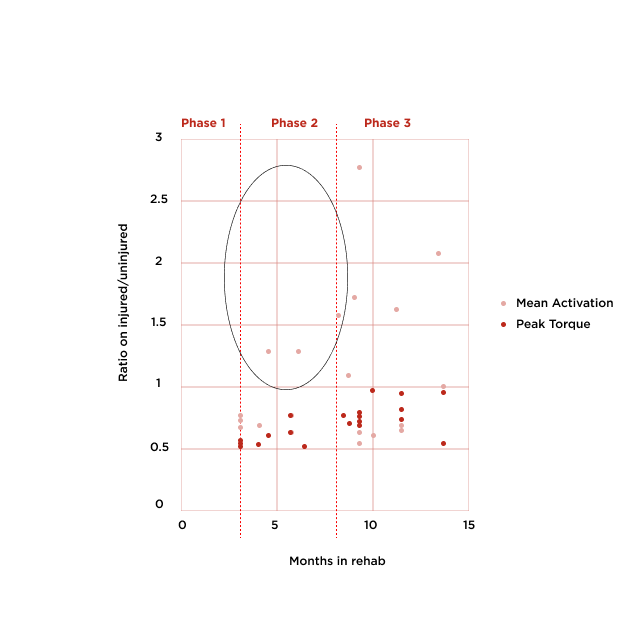

After testing, we determined that there are 3 distinct phases (see Image 1).

0-3 months – low performance/low neuromuscular effort

Patient is recovering from surgery and doing basic exercises to begin return to function to the knee extensors. Very low neuromuscular efficiency.

5-7 months – low performance/high neuromuscular effort

Patient is building muscle and strength. However, neuromuscular pathways are not efficient. Though there are strength gains, the activation required is high compared to healthy leg. Injured leg fatigues much faster than healthy leg. Neuromuscular efficiency is low however this is likely a required overshoot phase for neuromuscular function to return back to normal.

9+ months – high performance/lower neuromuscular effort

Patient is moving onto functional movements and neuromuscular pathways are returning. Strength and performance is improving and required neuromuscular effort is lower. This is indicative of massive improvements in neuromuscular efficiency as the muscle is optimizing.

Idealized rehabilitation curve for neuromuscular recovery in red dotted line. What this curve depicts is return of neuromuscular function (Phase IàII) and then optimization of neuromuscular function (Phase IIàIII). Neuromuscular efficiency should continually improve over the 9 months of rehabilitation.

If an athlete starts to significantly deviate off of this idealized curve, a PT can know within a couple weeks instead of a couple months.

The Oro system can be used workout by workout by the rehabbing athlete. Effectively, every workout becomes an evaluation session and the PT has much more data to make workout prescriptions.

Right now, it is like we are expecting PTs to get to places faster on less gas with an outdated paper map. The Oro system is like a GPS system with turn by turn directions and traffic conditions to enable PTs to make the best decisions possible for their clients based on their own client’s response to their rehab sessions.

In patients that did not rehabilitate successfully (performance of injured leg did not end up within 10% of healthy leg by 9 months), we did not see an overshoot response in the 3-5 month phase like we saw in patients that successfully rehabbed after ACL reconstruction (Image 2). The overshoot was not present or massively delayed.

This is potentially a huge marker that can be incorporated into current PT practice to reduce the reinjury rate. Why?

Currently, athletes get a template 9 month rehab plan that is seldomly altered. Most of the time, a PT would have to wait several months to know if an athlete is rehabilitating on track. Furthermore, if successful rehabilitation is not reached by 9 months, the PT likely does not know what is holding the athlete back.

With the Oro system, a PT could know much sooner if rehab is not effective and make interventions as needed.

With regular use and frequent feedback for the PT, faster interventions can be made to support the athlete’s unique needs. We believe that this would overall improve outcomes, decrease the number of athletes returned to play when they are not ready, and athlete satisfaction.