Modern elite football has evolved into a faster, tighter, and more explosive game than ever before. The tempo has increased, player density has shifted centrally, and high-intensity actions now play a decisive role in transitions, chance creation, defending space, and winning duels. Yet, many coaches still evaluate performance using metrics that barely scratch the surface.

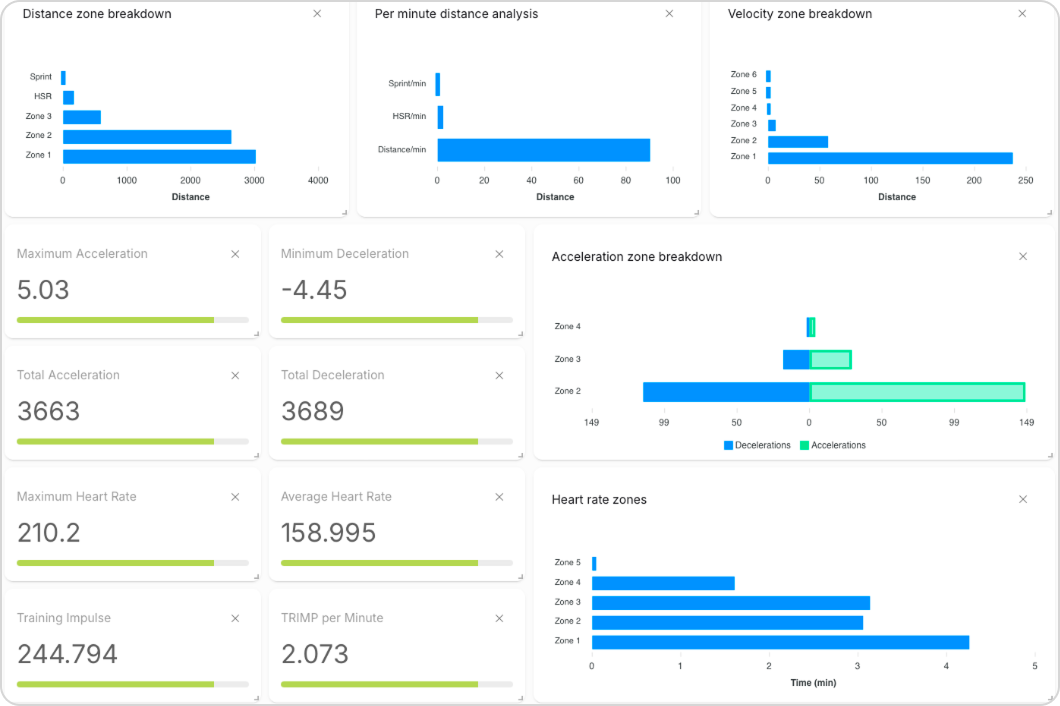

Traditional GPS velocity zones, distance covered above 25 km/h, number of sprints, high-speed running distance are useful, but dangerously incomplete (Figure 1). They capture how fast players run, but not how they move, why they execute specific actions, or what makes those actions decisive.

A recent narrative review published in International Journal of Sports Medicine by Alberto Filter et.al. sheds light on this mismatch and proposes a modern, contextual, and position-specific way to understand high-intensity actions (HIA). In this, two part, blog I will translate those findings into a practical coaching framework.

Figure 1 – Monitoring High Intensity Actions in Ultrax app

What High-Intensity Actions Really Are

Most teams define HIA using simple thresholds:

21–25 km/h

Duration > 1 s

Distances > 20–30 m

But this definition collapses when applied to actual football.

Football intensity ≠ running speed.

A defender accelerating from a static position to block a shot may never exceed 20 km/h, yet the mechanical and neuromuscular demand is maximal. A midfielder executing a tight 60° cut to escape pressure is not sprinting but it’s a high-intensity COD that taxes eccentric braking far more than linear top speed (Figure 2). A forward jumping for a header with a 4-step run-up performs a maximal explosive action, but it doesn’t appear in GPS “high-speed” categories.

High-intensity actions in football involve:

- Linear and curved sprints

- Accelerations & decelerations

- Changes of direction at varied angles

- Various jump types (two-leg, one-leg, run-up, body contact)

- Tackles, duels, aerial contests

- Movement from different orientations (rear, lateral, oblique)

- Rapid actions ending with a technical skill (cross, finish, clearance)

In short, high intensity is defined by the mechanical load on the body and the tactical purpose, not by arbitrary speed thresholds.

Why High-Intensity Actions Matter More Than Ever

The game we coach today is fundamentally different from the game played a decade ago. Everything has accelerated. Reactions are faster, decisions are made under greater pressure, transitions happen in seconds, and both defensive recovery and attacking runs demand repeated explosive efforts. Modern football simply leaves no room for slow moments, neither physically nor mentally.

Match data clearly supports this shift. Analyses from elite leagues between 2006 and 2013 show a substantial rise in match intensity, with high-intensity running increasing by 20 to 50 percent, sprint frequency rising by around 30 percent, and dribbling actions increasing by approximately 17 percent. Alongside this, the game now features more pressing phases, more frequent transitions, and a higher volume of explosive off-ball movement.

What is even more striking is what lies ahead. Performance models suggest that by 2030, players may be required to cover an additional 40 percent more high-intensity distance. In simple terms, the physical demands of football are increasing at a pace that many training systems are struggling to keep up with.

Tactics shape physiology and physiology supports tactics

Current tactical trends are pushing players into movement patterns that are far more explosive, more position-specific, and far more dependent on context than traditional performance metrics are able to reflect. The way teams now occupy space, apply pressure, and attack transitions has fundamentally changed how players are required to move during matches.

With greater player density in central areas, the game demands more duels, sharper changes of direction, and constant reactive micro-movements under pressure. At the same time, increased use of width and depth has created more space out wide and behind the defensive line, making curvilinear sprints a dominant movement pattern in today’s game. Faster transitions have led to more frequent and more intense recovery runs, often executed from compromised body positions, while structured pressing systems have turned short, repeated maximal bursts into a regular feature of match play rather than an exception.

These are the moments that decide matches. Winning a crucial duel in stoppage time, timing a run in behind with precision, closing space just before a shot is taken, or attacking a cross with a powerful run-up header are actions that shift momentum and outcomes.

The issue is that speed zones will never capture these moments. Football intensity cannot be reduced to running speed alone. It is not defined by distance covered, nor by sprint count. While those numbers can be useful, they fail to describe the true intensity of the game.

The real demands of football are found in how players move, the orientation they start from, their initial velocity, whether the movement follows a curved or linear trajectory, the angle and exposure of a change of direction, the technical action that finishes the movement, and the tactical intention behind it. This combination is what separates a player who is simply fit from one who is truly decisive.

This is why understanding High-Intensity Actions is essential in high-level coaching. Not to increase volume for the sake of volume, but to train the specific explosive actions that consistently win matches.

Speed Doesn’t Equal Football Speed

One of the big blind spots in football preparation is assuming that traditional athletic testing automatically transfers to the pitch. It doesn’t. Football speed is not track speed, and match intensity has very little in common with what most testing batteries evaluate.

Let’s break it down.

Straight-Line Sprints ≠ Real Match Sprints

Most elite-level sprints in football are nothing like the clean, straight, 0–30 m runs players perform during testing. In the game, sprints are usually:

- Curved, not linear

- From rolling momentum, not a dead stop

- From lateral or rear-facing orientations, not a perfect forward stance

- Ending with a decision or technical action, a cross, shot, duel, press, or recovery

Yet week after week, players are evaluated on a “track-style” setup that looks more like an athletics trial than football.

A winger doesn’t sprint like Usain Bolt.

A center-back doesn’t recover like a sprinter in lanes.

And full-backs rarely, if ever, sprint in a straight line for 30 meters.

So why do we keep testing them as if they do?

Standard Jumps ≠ Football Heading Jumps

CMJ and SJ are simple, reliable, and convenient. That’s why everyone uses them. But they tell you very little about a player’s ability to win an aerial duel or attack a cross.

Real heading actions are:

- Multiplanar, not vertical-only

- Executed with a run-up, not static

- Driven by trunk rotation and coordination

- Dependent on arm swing, not “hands on hips”

- Timed against a dynamic ball trajectory, not a flat force plate

A center-back’s match-winning header has nothing in common with a controlled laboratory jump test. If you want to measure football-specific explosive ability, a soccer-specific vertical jump gives you ten times more insight than a traditional CMJ.

Common COD Tests ≠ Real Defensive or Attacking COD

The classic tests, T-test, Illinois, 5–0–5, are fine for a general snapshot of agility. But they don’t represent the chaotic, position-specific COD patterns of real football.

They completely miss:

- Half-turn transitional COD used in pressing and recovery

- 30–90° cuts typical for central midfield movement

- Lateral sprints into the channel for full-backs and wide players

- Deceleration from high speed followed by curved reacceleration

- COD actions that finish with duels, tackles, interceptions, or shots

These aren’t small details they are the essence of football movement.

The gap between what traditional COD tests measure and what players actually do in matches is enormous. And yet, most testing batteries still rely on outdated drills that belong more in classes than high-performance environments. If our testing doesn’t match the real movement demands of the game, then our training won’t match them either. And if our training doesn’t reflect the true intensity, complexity, and directionality of football, we end up preparing athletes for the wrong sport. Modern performance requires modern testing. Football-specific movement requires football-specific evaluation. And that shift is long overdue.

A Modern Framework: The “WHAT–HOW–WHY” Model

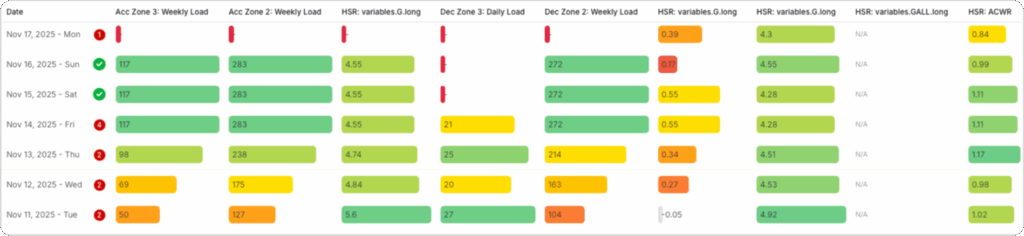

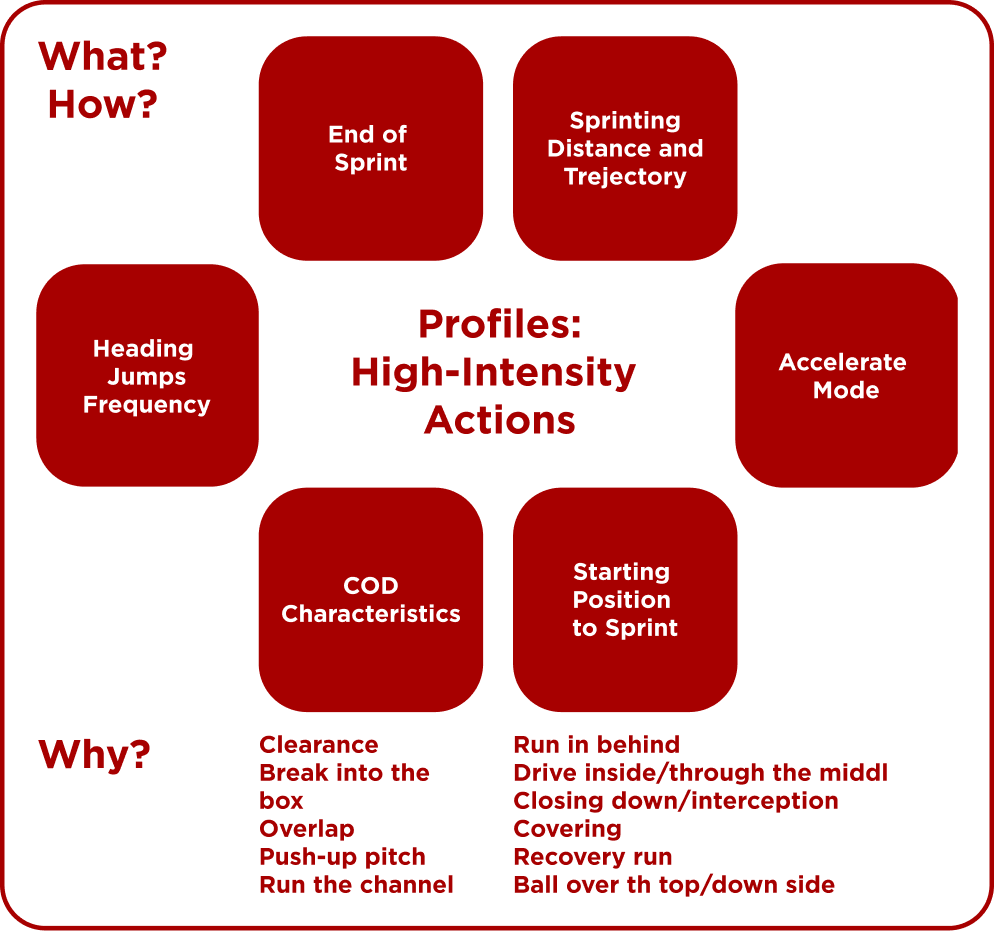

To truly understand high-intensity actions, and to train them in a way that matches the reality of elite football we need a framework that goes deeper than distance, speed zones, or simple sprint counts. The modern game demands that we look at each action through three lenses: WHAT the player does, HOW they do it, and WHY it happens in the tactical flow of the game (Figure 3).

This is where the “WHAT–HOW–WHY” model becomes incredibly powerful. It’s simple, practical, and gives coaches a clear structure for analysing, testing, and designing training that mirrors real match demands.

WHAT? Define the Action

Start by identifying the type of high-intensity action. Not the speed. Not the distance.

The action itself.

Examples of “WHAT” include:

- Curved sprint

- Linear sprint

- Change of direction (60°, 90°, 120°)

- Run-up, jump for a header

- Lateral or rear acceleration

- Aerial duel

- Explosive burst that ends with a cross, press, recovery, or finish

This step forces us to think like football coaches, not track coaches. It shifts the focus from athletic labels to football-specific actions.

HOW? Describe the Movement Characteristics

Once you know what the player is doing, the next step is understanding how they execute the action. This is where the biomechanics, the demands, and the context of movement live (Figure 4).

Ask questions such as:

- Distance:

- Short (0–10 m)

- Medium (10–25 m)

- Long (25–40 m)

- Trajectory:

- Linear

- Curved

- Starting velocity:

- From a dead stop

- From rolling momentum

- From high speed

- Starting orientation:

- Facing forward

- Lateral stance

- Facing backwards or half-turned

- Mechanical load:

- Is this mainly an explosive acceleration?

- A high braking task?

- A COD with heavy eccentric demands?

- Technical end-point:

- Does it finish with a cross?

- A duel?

- A clearance?

- A shot?

- A tackle, interception, or press?

This step exposes the true physical demands of the action. It also highlights why traditional tests often miss the mark: the “how” in football is almost never symmetrical, linear, or perfectly controlled.

WHY? Understand the Tactical Purpose

The final step is where everything clicks. Every high-intensity action has a tactical identity a reason it exists in the context of a match. If we ignore the “why,” we train movements without meaning.

Examples of “WHY” include:

- Recovering into defensive shape

- Pressing or counter-pressing

- Breaking into the box

- Running in behind

- Overlapping or underlapping

- Defending aerial balls

- Attacking crosses

- Closing passing lanes

- Creating space for a teammate

When coaches understand the “why,” training becomes more intentional, more position-specific, and far more transferable to match performance.

This framework transforms how we analyse players, how we build testing batteries, and how we construct training sessions.We focus on training football actions with clear football purpose, rather than generic athletic qualities. We measure what truly matters, not just what is easiest to track. And instead of guessing, we profile players based on the real demands of their specific role. This is modern performance coaching, grounded in real match demands, not outdated assumptions.

Zaključak

The first part of this blog has outlined a fundamental shift in how performance in football should be understood. The game has changed significantly, and with it the physical actions that decide matches. High-intensity actions can no longer be reduced to simple sprints or high-speed running. They are complex, context-driven, position-specific movements shaped by the tactical identity of the team.

Throughout this first section, it has become clear that the game is faster and more explosive than ever, that tactical evolution directly influences physical demands, and that traditional testing often fails to capture the movements that truly decide outcomes. A clearer framework, based on the WHAT, HOW, and WHY of high-intensity actions, offers a far more football-relevant way to understand, assess, and train these demands.

These insights are not just theoretical. They form the foundation for a meaningful shift in how training sessions are designed, how players are evaluated, and how teams are prepared for real match conditions. When physical preparation is aligned with the true nature of football actions, we stop developing generic athletes and start developing footballers who consistently dominate key moments.

And this is only the first part of the story.

What’s Coming Next

In the second part of this blog, we’ll move from understanding to application. We’ll break down:

1. Position-Specific High-Intensity Action Profiles

What center-backs, full-backs, midfielders, and forwards actually do at high intensity and how their demands differ.

2. Practical Implications for Coaches

How to use these insights to design sessions that match real match intensity.

3. Building Modern Testing Batteries

How to test curved sprints, soccer-specific jumps, real COD patterns, and integrated HIA tests that reflect the game.

4. How to Train HIA with Tactical Purpose

Turning WHAT–HOW–WHY into actual drills, conditioning formats, and position-specific training.

Part 2 will take everything from the first half and show you exactly how to apply it on the pitch with clarity, specificity, and purpose.

Scientific Resource:

Filter Ruger, Alberto & Olivares Jabalera, Jesús & Dos’Santos, Thomas & Madruga, Marc & Oliva Lozano, José & Molina-Molina, Alejandro & Santalla, Alfredo & Requena, Bernardo & Loturco, Irineu. (2023). High-intensity Actions in Elite Soccer: Current Status and Future Perspectives. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 44. 10.1055/a-2013-1661.

Explore more articles and insights at: https://www.ultrax.ai/blogs/