Yes, But Only If It Makes Sense

For the last two years I’ve been teaching at the Croatian Football Federation on UEFA licensing with football and fitness coaches, and honestly, this is the part I enjoy the most. When you sit with coaches who are in the trenches every day, dealing with real players, real problems, real training weeks, the conversation always becomes richer.

And one question keeps coming up every single time:

“Can we train hard during the in-season? Can we still improve something?”

My answer is very simple: hell yes we can. The real question is not can we, but do they actually need it? Because improvement at this stage of the season is not about chasing numbers, but about understanding the football context.

There is a lot of noise today around running metrics. Is running volume an important KPI? How much does it really matter if one team covers 110 km and another 118?

As always, context wins. And to answer this properly, I love quoting Luka Modrić, one of the best midfield players today. He said something like: “Football is played with the head. The physical part is important, but more important is where you run and how you read the game.”

And that’s the whole story. If your players read the game better than the opponent, you will simply run less, because you will arrive earlier, occupy better spaces, position yourself in a smarter way, and do more with less. Meanwhile, the team that is constantly reacting, constantly defending, constantly chasing, will accumulate large running numbers whether they want it or not.

In-Possession vs Out-of-Possession

Running Demands in the 4-2-3-1 Formation

When we look deeper into the physical demands of the 4-2-3-1, the story becomes even more interesting.

The study by Georgios Paraskevas (2021) analysed 26 elite matches and showed that running loads change dramatically depending on whether a team is in or out of possession, and this depends heavily on the position.

Out of possession, the biggest workload is on the wide defenders (WD), central midfielders (CM) i central defenders (CD).

- WD covered more very-high intensity running (VHIR) compared to when they had the ball.

- CM performed more VHIR and sprinting out of possession.

- CD not only covered more VHIR, but also performed more VHIR actions (nVHIR) and had longer VHIR distances (aVHIRd) when defending.

This shows that the “defensive engine” of the team—CD and CM—works significantly harder physically when the team does not control the ball.

In possession, the load shifts drastically:

- CM covered more total distance when the team was building up play.

- WM (wide midfielders) covered more total distance, more VHIR, more sprinting and performed more VHIR actions compared to out of possession.

Interestingly, wide defenders, wide midfielders and forwards registered more sprinting distance and longer VHIR efforts compared to central defenders and central midfielders, reinforcing the fact that offensive transitions and wide play demand explosive actions in space.

The key takeaway from Paraskevas’ work is simple: in the 4-2-3-1 formation, only the wide defenders are highly taxed both in and out of possession. Wide midfielders and forwards are taxed mainly in possession, while central defenders and central midfielders are taxed mainly out of possession.

Now, let’s connect this to something we all watched. Take the Champions League example everybody remembers. Real Madrid ran the least in the quarter-final second legs. Arsenal covered 72 miles, while Real managed only 66.8. In the first leg, Arsenal passed 70 miles again, while Real stayed around 63.

And here comes the twist, Real Madrid lost both games.

Yes, they have world-class players, but when you enter a competition like the Champions League, where the tempo is higher, the transitions are faster, and the physical requirements are unforgiving, running volume suddenly becomes an important KPI. Not in isolation, not as a magic number, but as a reflection of intensity, intention and competitiveness.

The data published by beIN Sports paints the full picture:

Real Madrid ran the least of all eight quarter-final teams, and the physical disparity matched their worst run in the competition in years. They only out-ran their opponent once all season, and this Champions League campaign ended with six defeats, the most in the club’s history for a single edition.

In contrast, the teams driving the tempo of the competition, Dortmund, PSG, Arsenal, Aston Villa, Bayern, consistently covered higher distances. Borussia Dortmund ran over 76 miles in their comeback attempt against Barcelona. PSG logged more than 71 miles trying to break Aston Villa’s defensive block. Even Inter Milan, one of the “lower” running teams, still reached 70+ miles, comfortably ahead of Real’s numbers.

So the message here is not that “running more means winning” football is never that simple. The message is that your physical KPIs must match the demands of the competition you are trying to win.

In domestic leagues, you might get away with different models. In the Champions League, you won’t.

This brings us back to the main idea of the blog: context defines load, load defines adaptation, and adaptation defines readiness. There is no universal number that fits every team. Real Madrid and Arsenal are perfect opposites, each successful in their environment, but when they met in a competition that demands constant high-speed running, physiology mattered. (https://www.beinsports.com/en-us/soccer/uefa-champions-league/articles-video/real-madrid-exposed-once-again-after-distance-covered-in-arsenal-match-is-revealed-2025-04-17).

Now let me bring this even closer to home, the Croatian league. This is maybe the most interesting part of working inside the Ultrax ecosystem. You talk with coaches daily, you see planning sheets, GPS metrics, microcycles, and very quickly you realize something important: two teams can have completely different weekly loads and still be equally successful.

I’ve seen teams with over 40 km per week in-season and teams who barely touch 25–30 km. And here’s the twist, both groups win games, both groups keep players fit, and both groups have similar injury rates.

How do you explain that?

Two teams can choose two completely different pathways and still end up in the same place because the game model, the player profile, the pitch size, the squad depth, the session structure, and the readiness of the players all dictate what works. When people copy Premier League numbers into the Croatian league without respecting the difference in tempo, number of transitions, weather conditions, pitch quality, and training schedule, we get false comparisons.

So back to the original question — can we have a load day during the in-season?

Yes. And not only can we — sometimes we absolutely should. But only when it fits the needs of the players and the needs of the game model.

A loss of sharpness in speed profiles can be addressed through targeted speed-strength work.

Declines in repeated high-intensity endurance may require a controlled conditioning stimulus.

When the tactical model emphasizes large transitions, load days are often best delivered in a football-specific context.

During congested periods with players nearing fatigue thresholds, removing the load day can be the most effective option.

There is no “yes or no” answer, only the right question:

What do my players and my game model need right now?

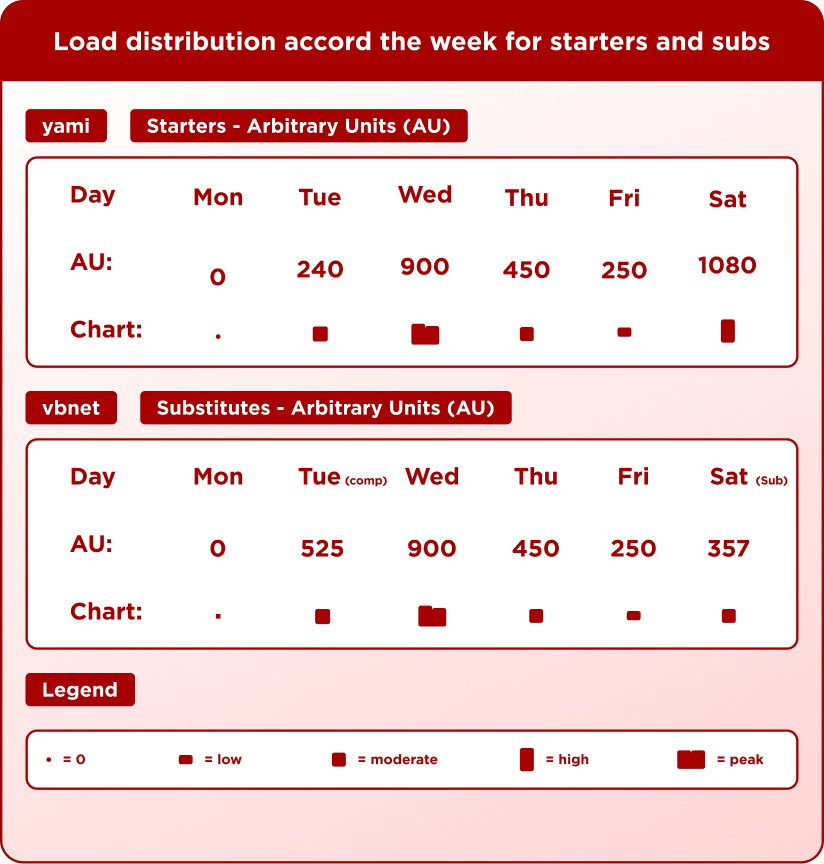

When you look at the day-to-day reality of Croatian second-division football, the microcycle often has a very simple and predictable rhythm. On Tuesday, the squad splits depending on minutes played. Those who played less or didn’t play at all get a compensation session — usually a mix of football actions and conditioning to bring them closer to match load.

The starters, meanwhile, go through a short regeneration session, often 30–40 minutes of bikes, mobility, and light technical work. It doesn’t sound like much, but the intention is clear: reset the system and balance the squad.

Wednesday is the only true “hard” day of the microcycle and everything revolves around it. In the morning you’ll typically see a focused gym session, two main strength lifts, some auxiliary work, nothing crazy, just enough to maintain strength without creating unnecessary fatigue. The main work comes in the afternoon: the key training of the week.

This is where intensity is highest, the tempo is closest to match demands, and many teams add a running supplement at the end, whether that’s HSR exposure, sprint efforts, accelerations, or a small RSA block. If there is one day in the week where players really accumulate physical load, this is it.

Weekly Load Summary

Starters: ~1800–2100 AU / Non-starters: ~2000–2400 AU (because they carry Tue compensation + extra work on Sat)

On Thursday, everything shifts toward tapering. Coaches keep the volume low but the quality high. This day is often filled with finishing, free-kicks, and short technical blocks with long rest intervals. The goal is simple: maintain sharpness without adding fatigue. Every step from Thursday onward is aimed at arriving on Saturday in the right state . Friday is the classic MD-1 structure that almost every Croatian club follows. Set pieces, organization, a bit of rondo, some activation work, and in many clubs today, a small neuromuscular stimulus , a few controlled jumps and one maximal sprint. It’s not fatigue-inducing; it’s just enough to wake up the system and prepare players for the match.

What a High-Load Day Really Looks Like: Interpreting the Wednesday GPS Session

When you look at this Wednesday afternoon training session, the first thing that stands out is how uniformly high the load is across the entire team. There are no positional markers,no tactical labels, ust raw numbers. And when raw numbers look like this, you immediately know one thing: this was the overload day of the week.

Across roughly twenty players, total distance ranges from 7,700 m to 9,200 m, high-speed running (HSR >20 km/h) from 570 m to 1,206 m, and sprint distance (>25 km/h) from 265 m to 535 m.

This type of session is the backbone of an in-season microcycle, an MD-3 overload stimulus that consolidates aerobic work, mechanical load, and neuromuscular exposure in one place so that the rest of the week can progress toward freshness.

Total distance is the easiest metric to interpret. Here, players fall mostly between 8.2–9.2 km, with only a few dropping below 8 km. When the majority of players cross the 8.5 km mark in training, it means the pitch size was large, the games were extended, and the coach allowed phases of continuous play without heavy stoppages.

The one or two athletes above 9,100 m represent the upper slice of total volume, the ones who either naturally roam more, or who simply accumulated a bit more work because of their role in the exercises.

example :D)

On the opposite end, players below 8,000 m likely experienced slightly modified exposure, fewer transitions, or shorter involvement in continuous games—but still enough to call the day “high load”.

This is where the session’s true intensity starts to reveal itself. HSR values ranged from ~570 m all the way up to 1,200 m. In most professional environments, anything above 700–800 m is already a substantial dose on a training day. So when multiple players surpass 900 or even 1,000 meters, you know the design intentionally exposed them to high-speed work.

This typically means:

- Large-area transitional games

- Repeated offensive–defensive waves

- Big spaces behind defensive lines

- Or explicit running blocks embedded inside the session

When more than half of your squad touches 800–1,200 m of HSR, you’ve provided a strong mechanical load for tissue adaptation, something players need to tolerate match demands.

The sprint distances here—between 265 and 535 meters—tell a very clear story. These are match-like sprint numbers, not warm-up or “technical day” values. A few players above 480–520 meters received a very high neural stimulus. These are the athletes who will need closer monitoring the next day, because sprinting volume carries the highest neuromuscular cost.

This level of sprint exposure usually requires:

- 48–72 hours to fully consolidate

- A freshness check on MD-2

- Good sequencing of strength work around the sprint day

But again, this is exactly what you want on the middle day of the week: a well-timed overload window.

Total Distance Groups (approximate):

- High Load (> 9000 m): ~4 players

- Moderate Load (8400–9000 m): majority

- Lower Load (< 8300 m): ~3 players

HSR Groups:

- High (> 950 m): ~3–4 players

- Moderate (750–950 m): majority

- Low (< 700 m): ~4 players

Sprint Distance Groups:

- High (> 450 m): ~3 players

- Moderate (350–450 m): most

- Low (< 330 m): ~4 players

You can all agree that this session looks like a proper load day. Total distance, high-speed running, sprint values, everything is clearly pushed upward. And this is exactly where the conversation around “cut-offs” and GPS standards becomes interesting.

In the last few years we’ve started labeling things as too high, too low, optimal, red zone, above threshold, and so on.

Some clubs even design training sessions with the primary goal to hit certain GPS numbers, almost like trying to copy the physical profile of a match.

But here’s the reminder we all need:

GPS load is not the same as training stimulus.

If your session is built only to “simulate” the game, you may miss the chance to actually develop something. Sometimes a drill with lower total distance but high mechanical load, or high eccentric action, or high deceleration density gives you more value than chasing arbitrary kilometers.

The second point is about habitual loading. Every team has their own patterns, what I like to call “loading habits”.

When you zoom out, ask yourself:

- Is this load normal for my team or an outlier?

- Is this load aligned with our game model?

- Does this load push or exceed individual profiles?

- Is this load development-driven or compensation-driven?

And the fun part of this example?

On Saturday, the team won 3:0. That’s always the punchline, you can debate numbers, philosophy, thresholds, but at the end of the day… if the players feel good, respond well, and perform, it’s working.

A big thanks to my friend Vedran Kovačević and his club BSK Bijelo Brdo for sharing his data with us and allowing this discussion to happen. This type of openness between practitioners is what pushes our field forward.

If you’re interested in a related topic, you may also find this blog useful: https://www.ultrax.ai/trainings/does-running-performance-reflect-game-performance/