Summary of Previous Blog Post

Running plays a vital role in overall health, aiding in weight reduction and the development of functional abilities. For beginners, it’s essential to start gradually to avoid injuries and overexertion. Selecting the right footwear and clothing, which should be both comfortable and functional, is crucial for an effective running experience.

Setting the correct pace and intensity is important to maintain long-term running habits with minimal injury risk. Additionally, incorporating proper warm-up routines and stretching exercises after running helps in muscle recovery and injury prevention. Setting realistic goals is key to steady progress and maintaining motivation. Proper running technique is fundamental for efficiency and injury prevention. In this post, we will dive into the details of proper running form, providing you with the knowledge to enhance your running performance and enjoyment.

Introduction to Running Technique

One of the most crucial aspects of running is mastering proper running technique. Developing this technique over time is essential for several reasons. First, proper technique allows you to use the least amount of energy, making your runs more efficient. This means you can run longer distances without feeling as fatigued. Second, correct running form helps your body absorb and manage impact forces from the ground. This reduces the risk of common running injuries such as shin splints, knee pain, and stress fractures. Lastly, with proper technique, your movements become more streamlined and effective, allowing you to run faster and with greater ease.

Proper Posture: Straight Back, Relaxed Shoulders, Upright Stance

The position of the head and spine is often overlooked in proper running technique. Most attention is usually given to the movements of the legs, while the arms, head, and torso, including the spine, are frequently neglected. Although the legs propel the body during running, the force from the ground must be correctly transferred to the body’s center of gravity to enable forward linear movement. The neutral position of the spine plays a crucial role in this process. During running, the torso should be upright, with minimal lateral and rotational movements.

The main movements occur in the hips and shoulders. The spine should remain neutral, the chest firm, the head aligned with the spine, the shoulders relaxed, and the entire torso stable. Depending on the discipline, the whole torso may lean forward at an angle of 0-10°. It is important to emphasize and understand that this tilt is achieved at the hips, while the spine remains neutral. Achieving a neutral spine position can be more challenging than it appears due to its complexity and the fact that many postural issues affect its neutral position.

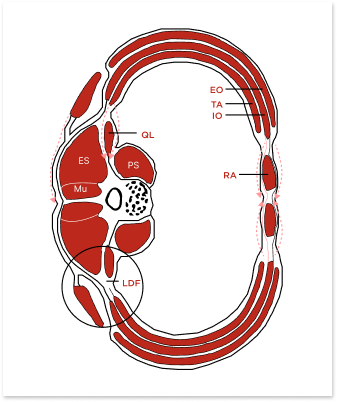

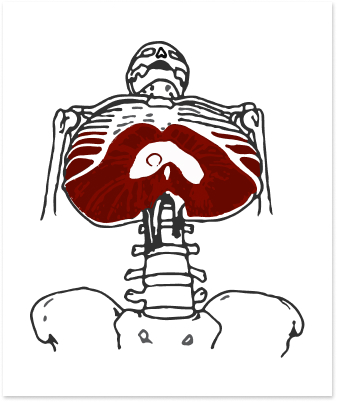

To maintain proper posture, we must have active muscles in that area. Michaud & Thomas C., authors of “Injury-Free Running” have listed the muscles and their importance for maintaining proper posture, the iliocostalis and longissimus muscles are important while running, as they prevent excessive forward lean of the torso. Collectively, these muscles are referred to as the “erector spinae” (Latin for “erect the spine”). The quadratus lumborum and the multifidi are powerful stabilizers of the spine and are exercised while performing side and conventional planks.

Additionally, core muscles are crucial. These important muscles wrap around the torso, connecting our rib cage to our pelvis. The force created by the internal oblique (IO), external oblique (EO), and transversus abdominis muscles (TA) is transferred through the lumbodorsal fascia (LDF) to help stabilize the entire lower spine (A). Though rarely discussed, the pelvic floor (not shown) and diaphragm (B) are also important core muscles. The diaphragm works with the transversus abdominis to help stabilize the core and plays an important role in running, particularly sprinting. (Muscle abbreviations: ES = erector spinae; Mu = multifidi; PS = psoas; QL = quadratus lumborum; RA = rectus abdominis, the six-pack muscle.)

Arm Position

The arms neutralize the rotational movements created by the legs during running. Since running is an asymmetrical movement, one hip is flexed while the other is extended. The arms compensate for these rotational forces by synchronizing the forward swing of the left arm with the forward swing of the right leg, and vice versa. A stronger leg swing is accompanied by a stronger arm swing.

Arm movements are executed exclusively at the shoulders, and the angle at the elbows remains constant, around 90°. The arms move forward and backward, not left and right. In the forward swing, the arms go towards the chin but do not cross the body’s midline (sagittal plane). In the backward swing, the focus is on the elbow leading the movement without extending the arm at the elbow. At the body’s midline, the arms are at hip level, and the shoulders remain relaxed the entire time.

Hips Function

The hip is a crucial joint for running, and without its proper function, success and injury prevention are very questionable. Elite runners have a wide range of hip flexion and extension, as well as the ability to perform strong external rotations. During running, the movement of the legs begins from the hip by lifting the knee, not by swinging the lower leg. Fast running increases the hip flexion of the swinging leg. Lifting the knee keeps the lower leg under the pelvis, shortens the force lever, reduces the load on the hip flexors, lengthens the stride, and increases speed.

Problems can arise if the hip does not function properly or if the hip flexors are too weak. In such cases, the knee-lifting motion becomes impossible, and the leg swings extended at the knee. As a consequence, the following issues may occur:

- Shortened stride, increased number of steps, and additional load on the hip flexors.

- The force lever lengthens, further burdening the already weak hip flexors.

- Fatigue of the hip flexors, which can cause external rotation of the leg, shifting the work to the adductors.

- Shorter strides, causing lateral and rotational movements of the lower leg and foot.

- This heel contact deactivates the Achilles tendon and the hip flexor tendon, transferring the force to the skeleton, which can damage the knees and/or the lumbar spine.

- The extended leg touches the ground with the heel in front of the body’s center of gravity, causing braking.

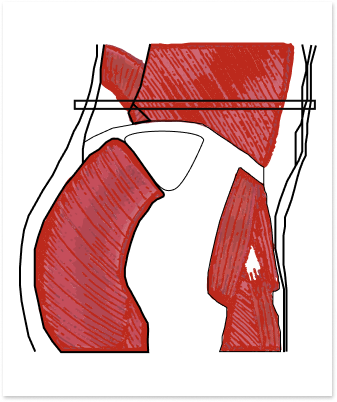

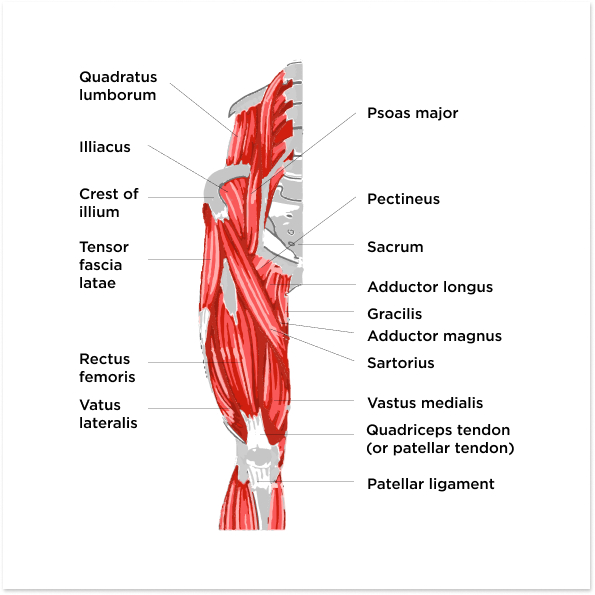

Image 3 Upper leg muscles

Now that we understand the function of the hip and thigh in running, let’s take a closer look at which muscles are responsible for these movements. Michaud & Thomas C., authors of “Injury-free running” have listed the muscles and their importance for proper leg function:

The iliotibial band (ITB) and the iliopsoas: The ITB acts as a broad tendon that transfers the force generated in the gluteus maximus and tensor fascia latae muscles to the leg and thigh. It has multiple attachments to the femur and plays an important role in preventing the opposite side of your pelvis from dropping too much while you run. The iliopsoas is a powerful hip flexor, and because of its multiple attachments to the lumbar spine, the psoas acts as a spinal stabilizer.

Muscles of the front of the thigh: The adductors consist of the adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, gracilis, and pectineus. The vertical portion of the adductor magnus is also called the “ischiofemoral portion,” since it runs from the ischium of the pelvis to the lower portion of the femur. The quadriceps consist of four different muscles: vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis, and rectus femoris. The vastus lateralis is by far the largest of these muscles and plays an important role in shock absorption while running.

The rectus femoris is the only quadriceps muscle to cross the hip joint, and it is one of the few hip muscles to possess a tendon that rotates appreciably. The rotation of the rectus femoris tendon allows it to store energy while your leg is extended behind you and return that energy to bring your swinging leg forward.

The patella: Located in the quadriceps tendon, the patella is the body’s largest sesamoid bone. Sesamoid bones are located inside various tendons all over the body, especially ones requiring high force output. They act to pull the muscle’s tendon farther away from the joint’s axis of motion, thereby improving the mechanical efficiency of the muscle. Think about a doorknob: If a doorknob is located close to the hinge, it is difficult to open the door. However, as the doorknob moves farther away from the hinge, less force is required to open the door. That’s essentially what sesamoids do. Sesamoid is Latin for “sesame seed.”

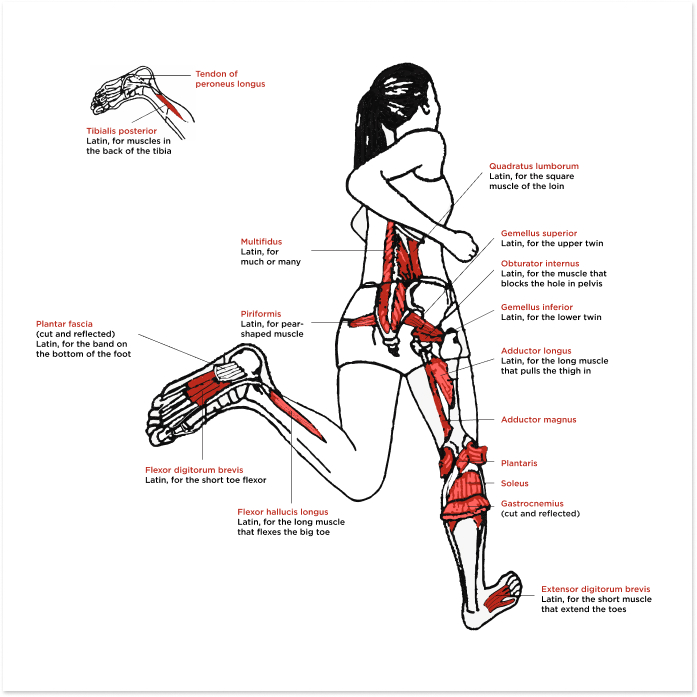

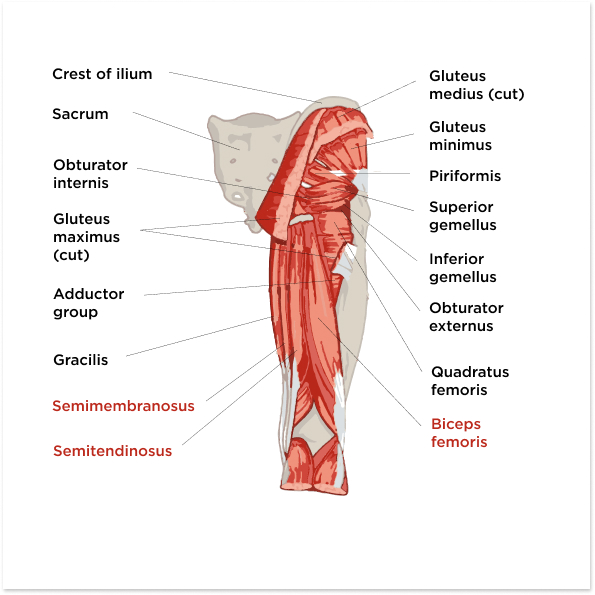

Muscles of the back of the thigh: The hamstrings are subdivided into the semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and biceps femoris (which contains a long head and a short head). Because it attaches so low on the femur, the vertical component of the adductor magnus behaves as a hamstring. The hip rotators are also important while running, as they prevent the entire lower limb from twisting inward too much.

Foot Function

The foot should always make contact with the ground using the front part, especially the pads under the toes. Before contacting the ground, the foot actively lowers, “searching” for the ground. Upon contact, the ankle should be flexible, allowing the heel to touch the ground. This stretches the Achilles tendon, which absorbs the force like a spring. In the concentric phase of the movement, when rising onto the toes, the absorbed force is released, making running more efficient.

Running on the heel or excessively on the toes without stretching the Achilles tendon increases the risk of injury and reduces efficiency. The term “dead” foot is often mentioned in running, referring to a foot that digs into the ground. To be a successful runner, you must strengthen and activate the foot and adopt proper ground contact.

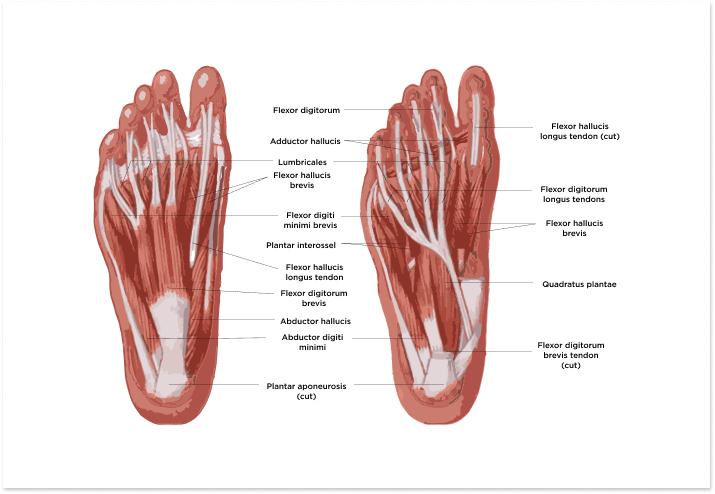

Muscles that are essential for proper foot function in running include the following: Strength and stability of the foot are among the most important prerequisites for walking and running, along with the calf muscles. In the feet alone, there are more than 100 muscles involved in movement. We will mention only the most important ones for running activity and proper foot function. The flexor hallucis brevis is important, as it contains two small sesamoid bones, which often cause problems in runners.

Weakness of the muscles of the arch is an extremely common cause of injury. Abductor hallucis weakness correlates with the development of bunions, while a weak flexor digitorum brevis is a common cause of plantar fasciitis. The tibialis posterior plays an important role in supporting the arch, as it possesses numerous attachment points to the center of the arch.

Rythmic Breathing to Avoid Excessive Fatigue

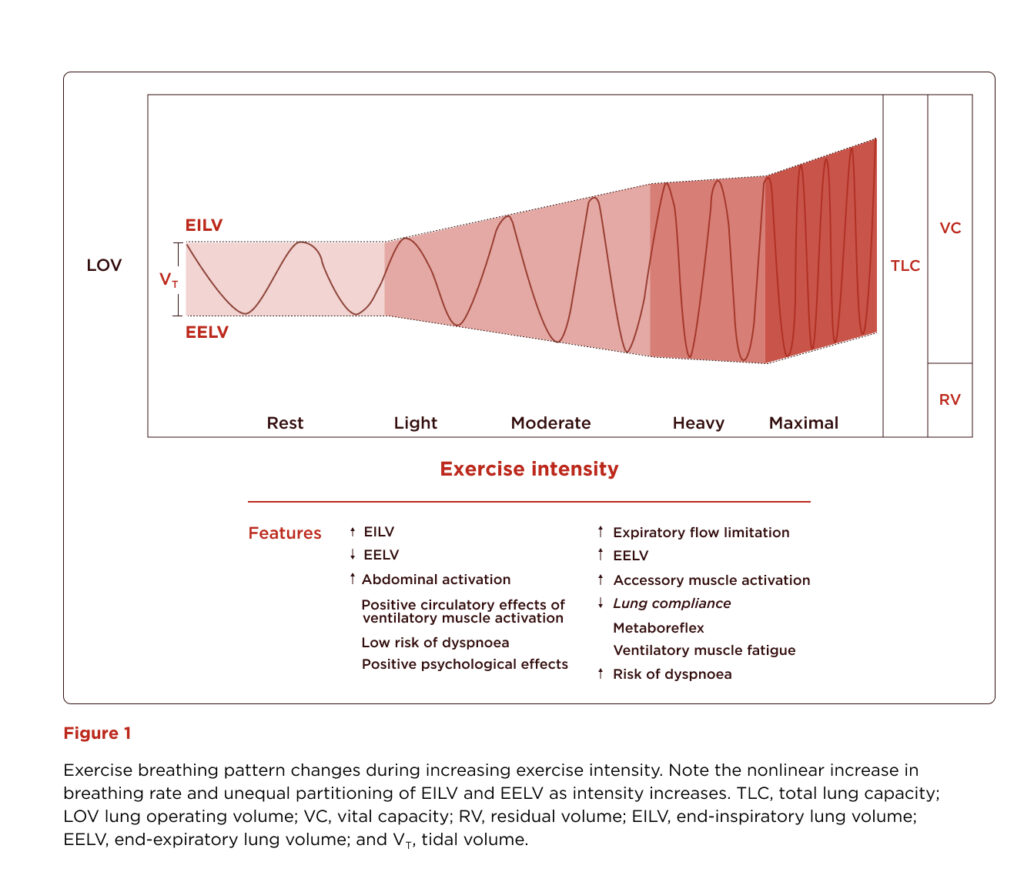

It’s fascinating to observe how our body reacts to increased physical exertion, especially when it comes to breathing. Since breathing ensures the transport of oxygen to cells, it logically speeds up during running. Maintaining a proper breathing rhythm is crucial for a successful workout. Breathing is something we can consciously control, which makes running easier and reduces fatigue.

How important is proper breathing during running? The rhythm of breathing is closely linked to the rhythm of running, so it’s essential to synchronize your steps with your inhalations and exhalations. Achieving this synergy helps balance oxygen consumption with its intake, allowing the body to function like a machine. It’s important that your steps match your breathing, for example, an inhalation lasting two steps and an exhalation the same (2:2 or 3:3), ensuring even distribution of effort on both sides of the body.

The quality of breathing can vary significantly among individuals, affecting lung capacity, the depth and frequency of breaths, and the ability to transfer oxygen to muscles. Although breathing quality is individual, techniques can improve performance while running. Instead of shallow chest breathing, deeper breaths involving the abdominal area should be practiced. Deeper inhalations ensure the body gets the necessary oxygen during exertion.

To improve your breathing technique while running, breathing exercises can help:

- Practice the ratio of breathing and steps while standing still (deep and slow breaths, breathing from the abdomen, not the chest).

- Then, start doing this during light walks, synchronizing your breathing rhythm with your steps.

- Once you master this technique, you can begin incorporating it into your running activities.

Protocols and Routines for Strengthening the Key Running Muscles

Our locomotor system is a complex structure composed of muscles, joints, and bones. To maintain joint and bone health and prevent pain, it is crucial to ensure our muscles are adequately conditioned and functional for running. Muscles play a vital role in facilitating movement by generating the forces necessary for joint and bone motions. By strengthening and conditioning these muscles, we can enhance our running performance and reduce the risk of injury, thus supporting overall musculoskeletal health.

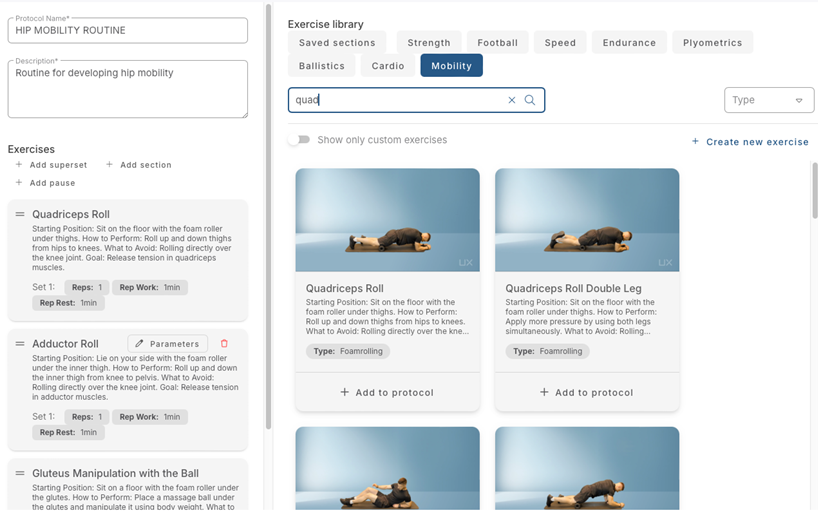

In this section, you’ll find fundamental exercises designed to strengthen and enhance the mobility of essential parts of the locomotor system, including the foot, ankle, lower leg, thigh, hip, and core. These exercises are crucial for developing the functional capabilities needed for running and other physical activities.

The protocols and routines provided are accessible through the Ultrax Training Builder. This innovative tool is invaluable for coaches, streamlining the creation of tailored training programs. Additionally, it enables a high level of individualization and precise monitoring for each athlete, ensuring optimal training outcomes.

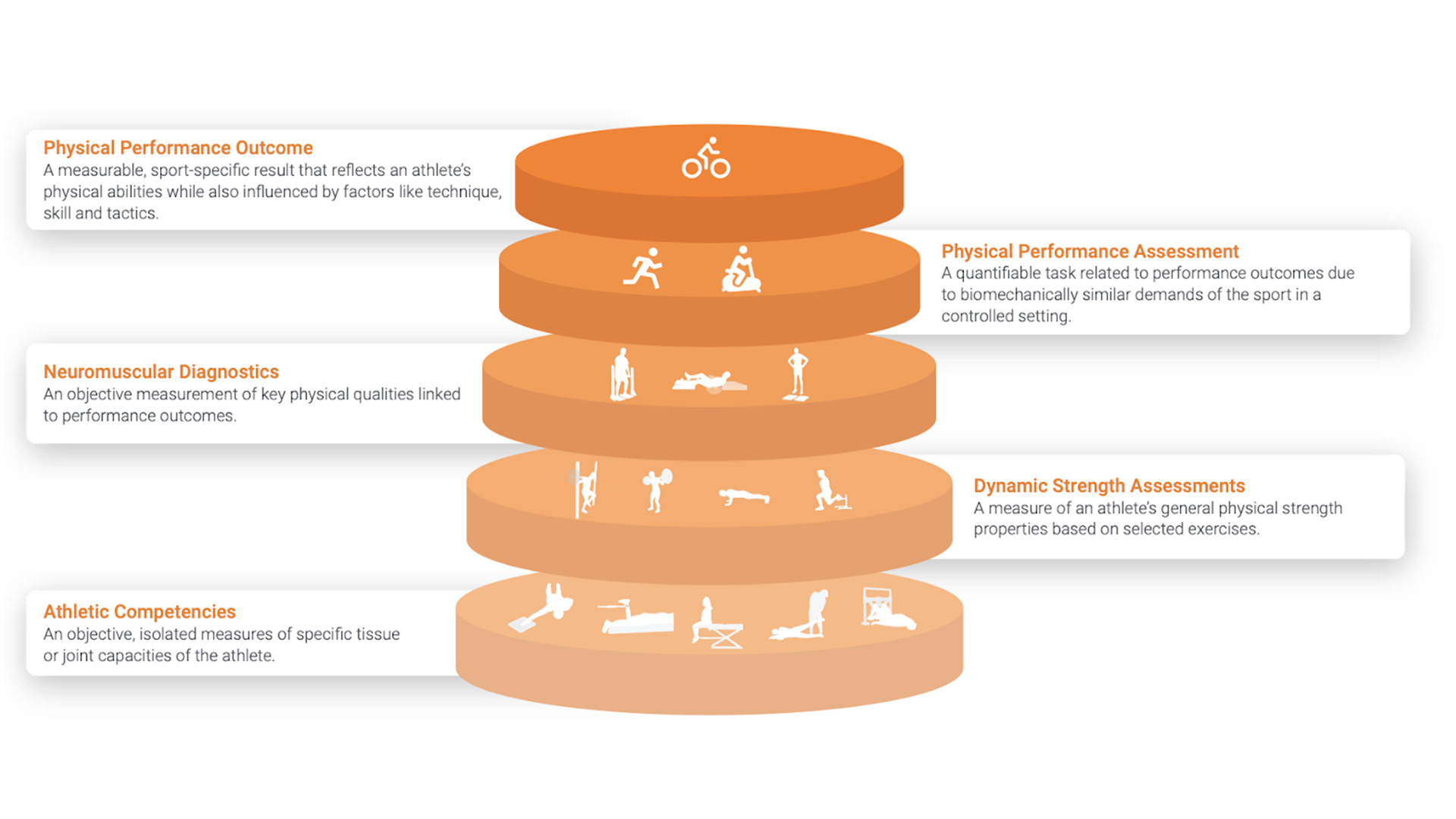

Definition of Protocols

To determine the load in training, there are general equations that should be used to load the musculature in strength and power training, as well as parameters for mobility and flexibility training. Since each of us is an individual both as an organism and as a person as a whole, these equations often provide incorrect calculations for determining the load in training. Therefore, it is necessary to test each athlete or recreational athlete to obtain results that will help determine the appropriate load.

For beginners in this entire process, we recommend that every recreational athlete engage a trainer for at least three months to master the basics and later be able to implement all the mentioned protocols on their own.

The following text contains training routines for developing mobility and strength protocols for important body regions involved in running. To make it easier to adapt the protocols to your needs, definitions for the protocols are provided in the subsequent text:

Mobility Protocol

Goal of the Protocol: To improve flexibility, joint range of motion, and reduce the risk of injury.

Duration of the Protocol: 4-6 weeks.

Frequency of the Protocols During the Week: 3-4 times per week.

Exercises:

- Dynamic stretches (leg swings, arm circles)

- Static stretches (hamstring stretch, hip flexor stretch)

- Foam rolling (quads, IT band)

Number of Reps: 10-15 reps for dynamic stretches.

Number of Sets: 2-3 sets.

Equipment Needed: Foam roller, resistance bands, mat.

RPE (from 0 to 10): 3-4 (light effort, focus on relaxation and range of motion).

Rest Periods Between Sets: 30-60 seconds.

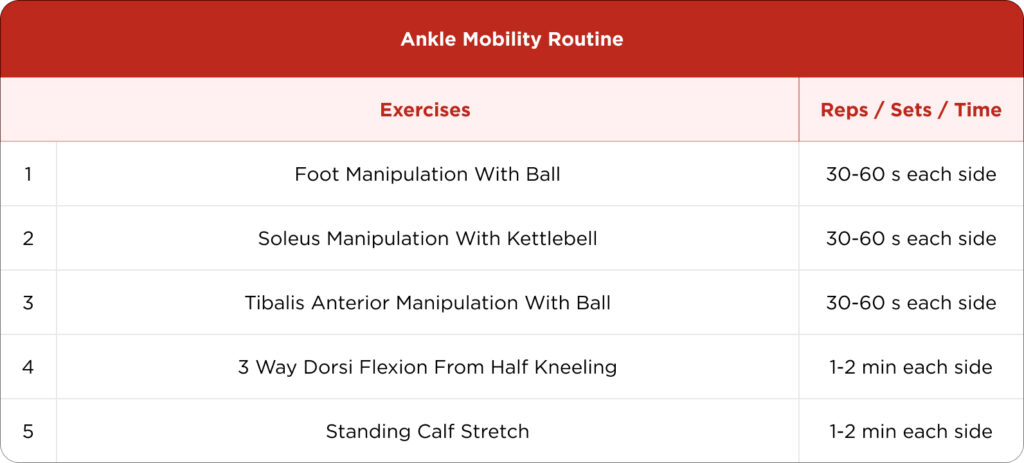

Watch the exercise examples: Ankle Mobility Routine

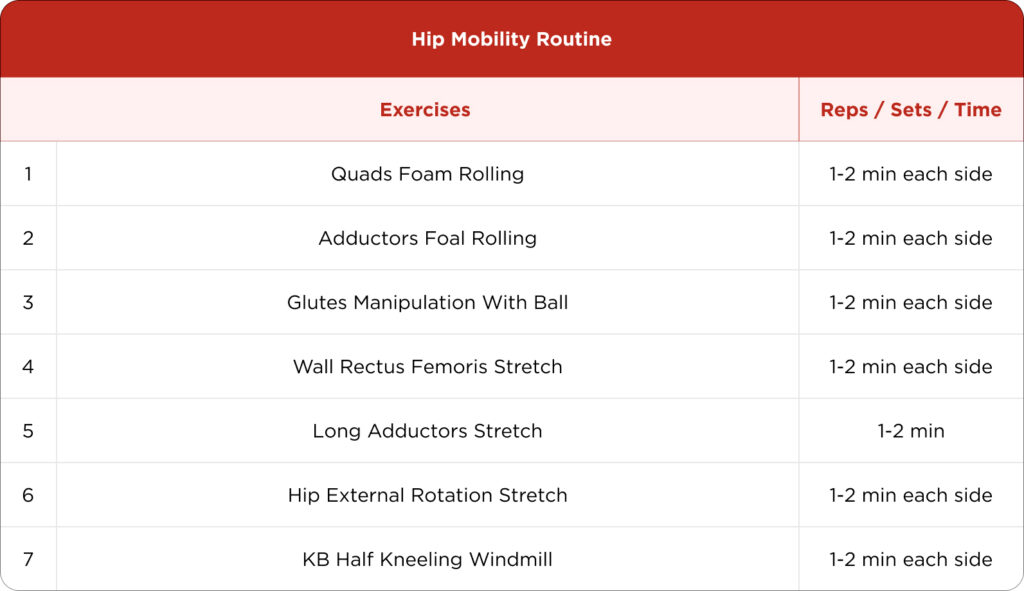

Watch the exercise examples: Hip Mobility Routine

Strength and Hypertrophy Protocols

Goal of the Protocol: To increase muscle strength and size.

Duration of the Protocol: 8-12 weeks.

Frequency of the Protocols During the Week: 3-5 times per week.

Exercises:

- Compound lifts (squats, deadlifts, bench press)

- Isolation exercises (bicep curls, triceps extensions)

Number of Reps: 6-12 reps.

Number of Sets: 3-5 sets.

Equipment Needed: Barbells, dumbbells, machines, kettlebell, resistance bands.

RPE (from 0 to 10): 7-8 (moderate to high effort).

Rest Periods Between Sets: 60-90 seconds.

Intensity RM: 60-85% of 1RM.

Force Velocity Zone and Meters per Second: 0.5-0.75 m/s for strength; 0.75-1.0 m/s for hypertrophy.

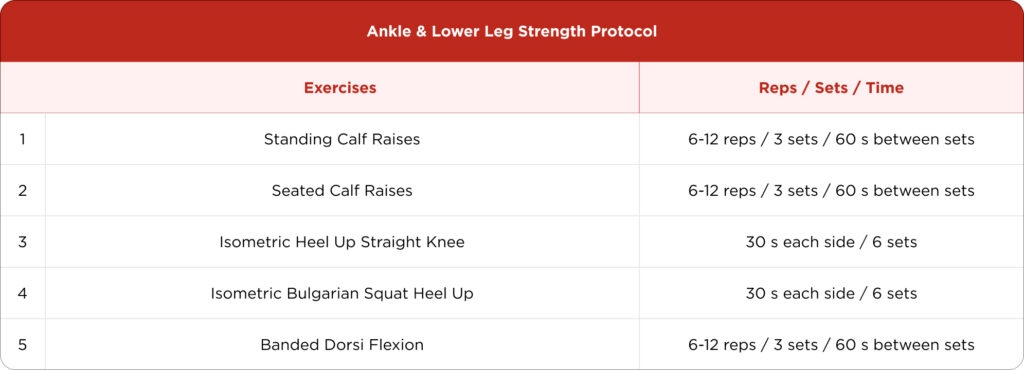

Watch the exercise examples: Ankle & Lower Leg Strength Protocol

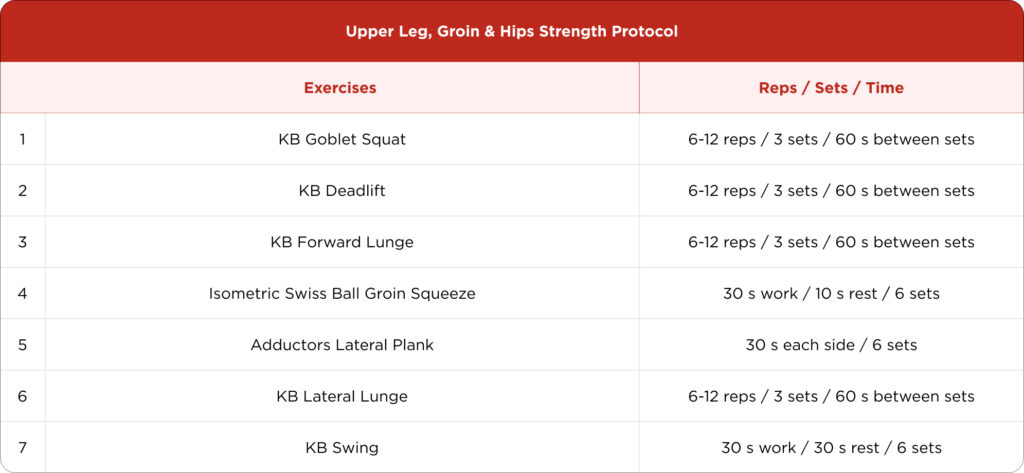

Watch the exercise examples: Upper Leg, Groin & Hip Strength Protocol

Core Protocol

Goal of the Protocol: To strengthen the core muscles, improve stability, and support overall athletic performance.

Duration of the Protocol: 6-8 weeks.

Frequency of the Protocols During the Week: 3-4 times per week.

Exercises:

- Planks

- Dead bugs

- Pallof press

Number of Reps: 15-20 reps.

Number of Sets: 3-4 sets.

Equipment Needed: Mat, elastic band.

RPE (from 0 to 10): 5-6 (moderate effort).

Rest Periods Between Sets: 30-60 seconds.

Watch the exercise examples: Core Protocol

Conclusion

Running technique is crucial for saving energy and minimizing the risk of injuries. However, as we can see, it is quite complex and requires constant focus while running. Our body is a perfect, complex system, and we must be mindful of everything we put into it and how we treat it, not only for running activities but also for the health of our muscles, bones, joints, and ligaments. Regularly performing the mentioned mobility and flexibility routines, as well as strength development protocols, will not only make running easier and minimize injuries but also elevate the quality of life to a higher level.

When we develop our body, the most important thing is discipline. With the expert guidance of a trainer, if we are beginners, we consequently develop our mind into the mind of a winner and a person who never gives up.

References

- Michaud, T.C., 2021. Injury-free running: your illustrated guide to biomechanics, gait analysis, and injury prevention. 2nd ed. Chichester: Lotus Publishing; Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

- Simon Brooker Coaching, 2023. What is running form? [online] Available at: https://www.simonbrookercoaching.com/news/what-is-running-form [Accessed 23 September 2024].

- Boschman, J. and Gouttebarge, V., 2013. The optimization of running technique: What should runners change and how should they accomplish it? Journal of Sport and Human Performance, 1, pp.1-10.

- SimpleMed, 2023. Muscles of the thigh and their actions. [online] Available at: https://simplemed.co.uk/subjects/msk/musculoskeletal-anatomy/muscles-of-the-thigh [Accessed 23 September 2024].

- Mountain Peak Fitness, 2023. Developing strength & stability in the foot, ankle, and lower leg. [online] Available at: https://www.mountainpeakfitness.com/blog/strength-stability-foot-ankle-lower-leg [Accessed 23 September 2024].

- Harbour, E., Stöggl, T., Schwameder, H. and Finkenzeller, T., 2022. Breath tools: A synthesis of evidence-based breathing strategies to enhance human running. Frontiers in Physiology, 13, p.813243. DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2022.813243.