Today we have a big problem with injuries in sports and today’s models and practical applications of injury prevention do not give us good results. In the most recent study of elite clubs (Ekstrand et al, 2022), we see a 100% increase in the proportion of hamstring injuries in the last 21 seasons (from 12% to 24% of all injuries), although a lot of investment is being made in models to prevent muscle injuries. In football, the re-injury rate is between 4 and 68% (Diemer et al, 2021), and the highest number of re-injuries occurs in the first month or two and these repeated injuries require 7-8 days of longer recovery (Bodendorfer et al, 2021; Chavaro- Nieto et al., 2021).

The risk factors that we thought were the best established for hamstring injury of all muscle injuries in sports have recently been confuted, with eccentric hamstring strength being the strongest risk factor in the literature to date. In 2019, Nicol van Dyk published a meta-analysis in which he showed that with the Nordic Hamstring exercise, we can prevent up to 50% of all hamstring injuries. In 2021, Impellizerri et al entered that meta-analysis and saw that the meta-analysis did not use only the best quality studies (Randomized Controlled Trials – RCTs) and excluded all other non-RCT studies. This new meta-analysis concludes that the results are conflicting and that, according to previous research, we cannot say that eccentric strength is such an important risk factor in hamstring injury. If we look at all the most common muscle injuries (hamstrings, rectus femoris, adductor longus, calf), then the only constant intrinsic risk factor for which we have the strongest evidence is a previous injury of the same muscle or some other injury of the lower extremities.

We should now ask a legitimate question, and that is why is a previous injury such a risk factor for future injury and what are the residual effects of a previous injury that have not been removed that put our body at greater risk?! Another question we also have to ask ourselves is, did we really believe that one exercise could have such an effect on reducing the risk of injury? That first meta-analysis (van Dyk et al, 2019) is a typical saying “Too good to be true”. Injuries are very complex and the body (system) is very complex and we cannot expect to find simple solutions for complex problems.

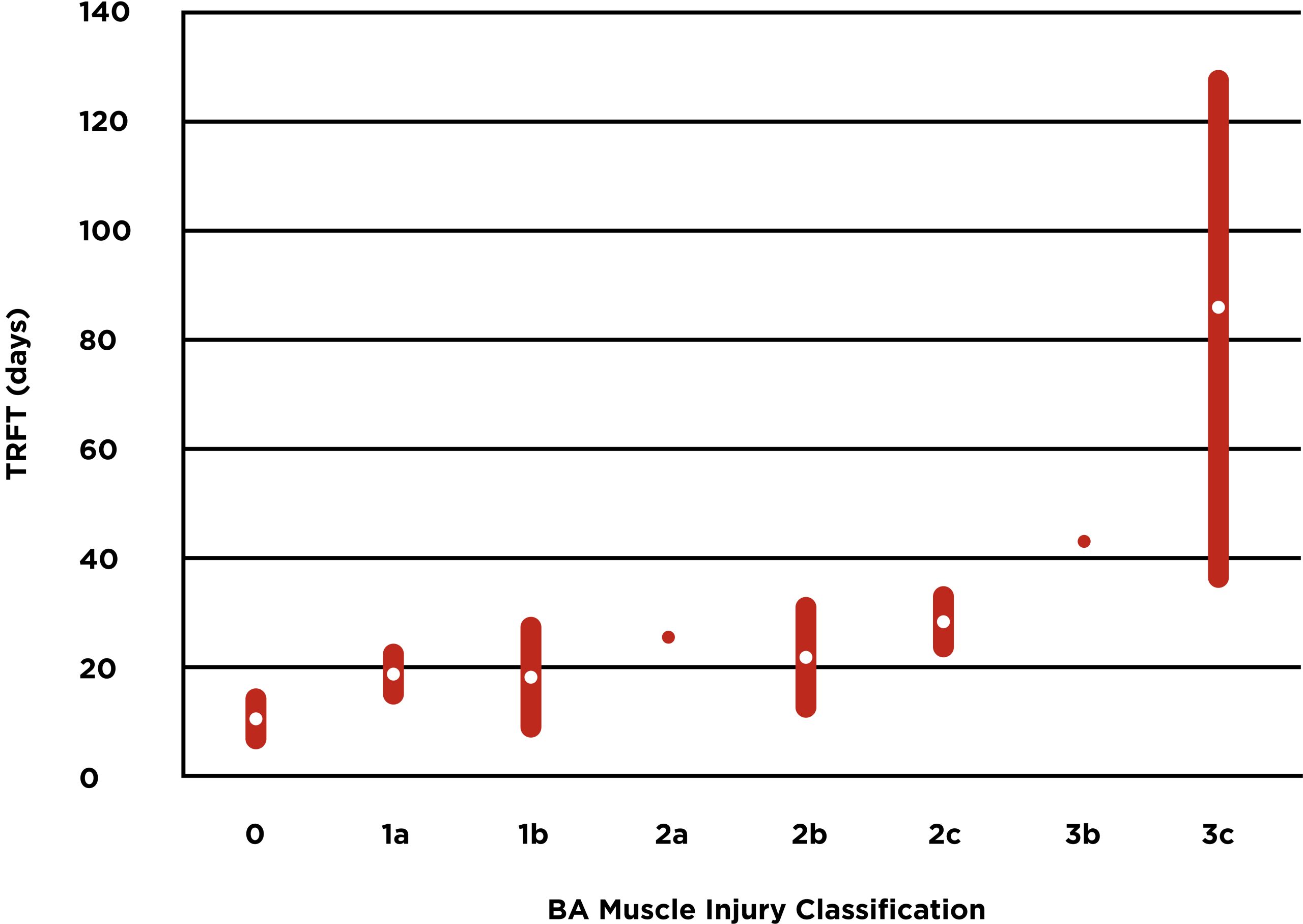

In the case of rehabilitation, we have various classifications of muscle injuries, the most famous ones are the “Munich Consensus”, “British Athletics” and the Barcelona classification system. Each of these systems brought something new to the classification models of muscle injuries, but what is interesting is that by testing the same systems in practice, we see a large standard deviation in the time of return from injury, especially when it comes to more severe injuries such as muscle – tendon junction tear or intratendinous injury (Pollock et al, 2016; Ekstrand et al, 2013; Shamji et al, 2021).

Table 1 is a graphical representation of the average and standard deviation of the time required to return to full training after an acute injury to the hamstrings, where we see that in the case of an intratendinous injury, we have a large standard deviation. Of course, a bad rehabilitation process is easily possible, but we have to ask ourselves if there are other factors in the background that influence the speed of recovery within the classification model. We should leave it to the scientists to deal with these questions. Maybe in the future, we will have better diagnostics and a smaller standard deviation, or maybe we should abandon universal models for muscle injuries because we know that all models are wrong. I don’t know, but what I do know is that each of us needs to focus on clinical skills and knowledge to complement these classification models that we currently have. Their advantage is that some of them differentiate more serious injuries from lighter ones (e.g. intratendinous injuries are more serious than myofascial injuries), but in order to reduce the standard deviation of the complete rehabilitation time, we will complete the picture of the patient’s structural and functional condition with a clinical examination and assess his return to normal activity.

This is a provocative blog that will make you start questioning the science in injury prevention and rehabilitation because I think the more we know, the less we understand. We should be very careful when we see publications and educations that talk about science-based practice because we see that we have very little solid evidence regarding rehabilitation and injury prevention. Of course, I am by no means saying that science should be completely rejected. Rehabilitation should be guided by science, but its limitations should be respected. We must not dismiss techniques that are not currently scientifically proven (such as manual therapy) because we may be limited by technology to measure the effectiveness of these techniques.

On the other hand, when the effectiveness of certain methods is measured in studies, then it is considered that we give one pill to exactly homogeneous groups according to one of the classifications and then we are surprised when we do not get the superiority of some methods over others. For example, according to the meta-analysis of Artus from 2010, we found equal effectiveness of walking with other methods used in the rehabilitation of non-specific back pain. Does this mean that we can do whatever we want in the rehabilitation process? In my opinion, absolutely not! The problem is that we gave different pills (rehabilitation methods) to a very heterogeneous group of subjects who were placed in the non-specific back pain group according to today’s classification. Probably none of these individuals are clinically the same even though they have the same diagnosis because they have different injury histories, different ages, psycho-social characteristics, etc. In the past, I was constantly looking for information about evidence-based practice, and today when I see it I am very skeptical. I know this is a blog that leaves more questions than answers, but it is a good introduction for future blogs where we will write about practical things respecting all these limitations.

References:

- Ekstrand J, Bengtsson H, Waldén M, Davison M, Khan KM, Hägglund M. Hamstring injury rates have increased during recent seasons and now constitute 24% of all injuries in men’s professional football: the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/02 to 2021/22. Br J Sports Med. 2022 Dec 6.

- Diemer WM, Winters M, Tol JL, Pas HIMFL, Moen MH. Incidence of Acute Hamstring Injuries in Soccer: A Systematic Review of 13 Studies Involving More Than 3800 Athletes With 2 Million Sport Exposure Hours. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021 Jan.

- Bodendorfer BM, DeFroda SF, Newhouse AC, Yang DS, Shu HT, Wichman D, Murphy JP, Milner JD, Hartnett DA, Gould H, Chahla J, Nho SJ. Recurrence of Hamstring Injuries and Risk Factors for Partial and Complete Tears in the National Football League: An Analysis From 2009-2020. Phys Sportsmed. 2023 Apr.

- van Dyk N, Behan FP, Whiteley R. Including the Nordic hamstring exercise in injury prevention programmes halves the rate of hamstring injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 8459 athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Nov.

- Impellizzeri FM, McCall A, van Smeden M. Why methods matter in a meta-analysis: a reappraisal showed inconclusive injury preventive effect of Nordic hamstring exercise. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021 Dec

- Pollock N, Patel A, Chakraverty J, Suokas A, James SL, Chakraverty R. Time to return to full training is delayed and recurrence rate is higher in intratendinous (‘c’) acute hamstring injury in elite track and field athletes: clinical application of the British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Mar.

- Ekstrand J, Askling C, Magnusson H, Mithoefer K. Return to play after thigh muscle injury in elite football players: implementation and validation of the Munich muscle injury classification. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Aug.

- Shamji R, James SLJ, Botchu R, Khurniawan KA, Bhogal G, Rushton A. Association of the British Athletic Muscle Injury Classification and anatomic location with return to full training and reinjury following hamstring injury in elite football. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2021 May 10.

- Artus M, van der Windt DA, Jordan KP, Hay EM. Low back pain symptoms show a similar pattern of improvement following a wide range of primary care treatments: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010 Dec.